On this date in 1924, diplomatic maneuvering, oil patch politics, and a dead American consul put two Iranian teenagers in front of a firing squad.

Largely forgotten today, the affair which prompted their execution helped Cossack commander Reza Khan‘s ongoing consolidation of power, culminating in another year’s time with his conquest of the Persian throne itself.

By the summer of 1924, he was by title Prime Minister and his domestic opponents could read the writing on the wall: he had made a premature bid for formal executive authority in 1923 only to be rebuffed.* At the same time, he was engaged in the perilous oil game with an attempt to use American companies to break a British oil monopoly.

On July 18, 1924, American Vice Consul Maj. Robert Imbrie and his civilian countryman Melvin Seymour were attacked by a Tehran mob while photographing a well which had become a Moslem devotional site for purported miraculous healings. Imbrie was beaten to death; Seymour was lucky to survive … and it soon emerged that soldiers from the nearby barracks had not only failed to protect the Americans but actually taken part in the assault.

Iran’s emerging strongman lost no time in making the most of it.

The event gave [Reza Khan] … the excuse for declaring martial law and a censorship of the Press … Numerous arrests have been made, chiefly of political opponents of the Prime Minister. (British military attache Col. W.A.K. Fraser)

It’s like Lenin said, you look for the person who will benefit and, uh, you know, uh, you know, you’ll, uh, you know what I’m trying to say …

Assuming one discerns some measure of design in the Imbrie murder, and the convenient outburst of anti-Baha’i paranoia that sparked the fatal incident, one can go a couple of different directions at this point.

-

That the Prime Minister’s foes, allied with British oil interests (the British angle was so widely believed in Iran at the time that press censorship forbade the incendiary charge), were firing up the rowdies in an attempt to shake his power. This 1924 American cable makes that case:

That Pahlavi’s own agents fomented the disorder. According to Michael Zirinsky‘s review of the case, another American official speculated that Reza Khan himself hoped a foreigner would die “so that he could declare martial law and check the power of the Mullahs.”“It had the earmarks from the beginning of an artificially inspired movement, of which the organized powers of evil were quick to take advantage in order to create disorder for the Government … Reza Khan found himself faced with a situation before which he was powerless. The fanaticism of the crowd was so incited by the continuous preaching of the Mullahs that any act on his part would have been interpreted as treason to Islam and prima facie evidence that he was a Bahai; hence his unfortunate orders to the military and the police not to intervene under any circumstances in religious demonstrations and under no circumstances to fire.”

Which, in the event, is exactly what happened.

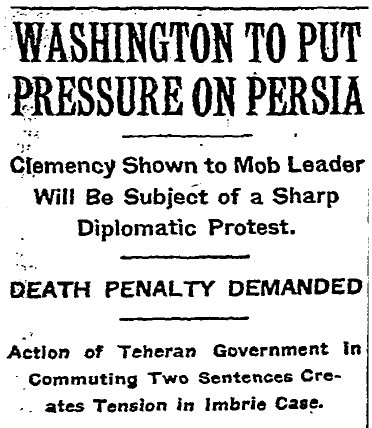

The U.S. made a great show of demanding exemplary justice, and it had the leverage to do so: Iran (how times change!) wanted American support and American oil exploitation.

Three were condemned to death for their parts in the riot, and after the first, a young soldier named Morteza said to have incited the mob, was shot on Oct. 2, the government announced leniency for the other two.

Not good enough.

“When you are dealing with a government like Persia … if you ask them to execute a Moslem for the death of a Christian … if they do it, you accomplish more for the prestige of your country than if they paid a million.” -a young Allen Dulles, in 1926 testimony to the U.S. House of Representatives.

At American insistence, those other two were recalled to death after all: 17-year-old mullah Sayyid Husain (various alternate transliterations – e.g., Seyid Hussein), who was supposed to have raised the riot-triggering “Baha’i well-poisoner” accusation in the first place, and 14-year-old camel driver Ali Reshti.

Zirinsky once again:

With the ending of the Iran-U.S. dispute by the execution of Ali and Husain on November 2, 1924, Reza was free to leave the capital city. He had support from the foreign legations, he had secured financing for the army, he had reestablished discipline in the Cossack Brigade, and by executing Sayyid Husain — a mullah — he had demonstrated his domination over the clergy … in the course of the next months’ campaign, he completed the unification of Iran and ensured that his government would get all the [Anglo-Persian Oil Company] royalties…

While the Imbrie affair was not the only critical event of Reza’s seizure of total power in Iran, it came at a critical moment in his rise … he used the murder to his best advantage.

And they all lived happily ever after.

* The future Shah’s future rival Mohammed Mossadegh was among the Iranian Majlis members who blocked Reza Khan’s attempt to rule Iran as a republic in 1923.

** “Blood, Power, and Hypocrisy: The Murder of Robert Imbrie and American Relations with Pahlavi Iran, 1924,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 18, no. 3 (Aug. 1986). Zirinsky quotes an American diplomat who believed Reza Khan was actually intentionally trying to create a situation where a foreigner would be killed, to give him a pretext for bringing his nation to heel with foreign support.

On this day..

- 1984: The Hondh-Chillar Massacre

- 1675: Boyarina Morozova, Old Believer

- 1907: Afanasi Matushenko

- 1715: Seven at Tyburn

- 1803: Ludovicus Baekelandt, Vrijbos bandit

- 1483: Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

- 82 BCE: The defeated populares of the Battle of the Colline Gate

- 1984: Velma Barfield, the first woman in the modern era

- 1801: James Legg, crucified ecorche

- 1972: Evelyn Anderson and Beatrice Kosin, missionaries

- 1920: James Daly, Connaught Rangers mutineer

- 2001: Mona Fandey, witch doctor

- 1963: Ngo Dinh Diem

The latest research shows that Melvin Seymour was an agent of the English company (ancestor of BP) which had an oil monopoly and wanted to sabotage RezaKhan’s rapprochement with the American company Sinclair. Imbrie was an intermediary for the negotiations with this company and his assassination convinced the director of Sinclair (Theodore Roosevelet’s grandson) not to continue negotiations with Iran. Reza Khan could not be the architect of a rapprochement with the Americans to diminish the influence of the English and at the same time kill an American. This accusation is false and the work of Englishmen who are not cited in this immensely geopolitical case.

So if the people executed were actually guilty of the killing, is it correct to simply categorize their executions as a political move? This article is rather poorly-written with a clear political spin on it. It makes many assertions without supporting them.

Pingback: ExecutedToday.com » Executed Today’s Third Annual Report: Third Time Lucky