On this date in 1575* a Japanese soldier was crucified under the walls of his castle … and entered his country’s folklore.

Torii Suneemon was a footman of the Okudaira family late in Japan’s fratricidal Warring States Period.

The Okudaira, allies of the wars’ eventually-victorious Tokugawa clan, found themselves besieged by the Takeda. This would result in the important Battle of Nagashino.

Kurosawa’s masterpiece Kagemusha imagines the Takeda where the (real) late daimyo Shingen was succeeded after his (real) 1573 death (fictitiously) by an imposter thief posing as the great commander. In the film, the imposter is unmasked and deposed, but witnesses the climactic Battle of Nagashino … and then makes a futile charge under the Takeda banner after that side is slaughtered.

After an initial Takeda attempt to take the fortress by storm, the Takeda settled in for a brief siege — knowing the defenders to have only a few days’ supplies on hand. Enter Torii Suneemon.

Under cover of darkness on the night of the 22nd-23rd, Suneemon slipped out of the Yagyu gate and picked his way through Takeda tripwires to escape the investment … and summon help.

Torii Suneemon embarks on his mission: 19th century woodblock print of Yoshitoshi‘s “24 Accomplishments of Imperial Japan” series. The same artist also depicted that event in this triptych.

He made it on the 23rd to Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga, who upon hearing his report pledged to dispatch a relief force the very next day.

Alas for him, Suneemon’s attempt to sneak back into the encircled fortress to deliver the good news was detected on the 24th, and he came as a prisoner to the Takeda commander. The Takeda prevailed upon their helpless captive to exchange his life for a signal service: approach the fortress walls and shout to the garrison that no help was on the way.

This Suneemon agreed to do.

The legends differ as to whether he walked on up to deliver this bogus bad news, or whether the Takeda lifted him up on a cross to impress upon their new agent the penalty for any funny business. Either way, Torii Suneemon had the last laugh: he immediately began hollering to the defenders that help was coming if they could just hang on a few more days.

Torii Suneemon goes off-script. Another Yoshitoshi creation, from here or from this detailed French post.

The besiegers, of course, crucified him immediately … but everyone could appreciate the doomed man’s heroism.

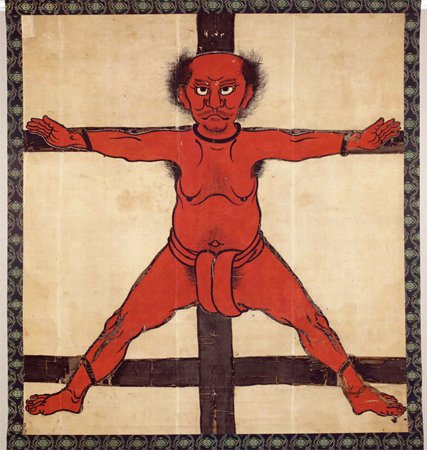

While the grateful Okudaira elevated his family to samurai rank, even an enemy Takeda commander who witnessed the event was so moved that he adopted the image of the defiantly crucified soldier for his battle standard.

Heck, there’s apparently even a Japanese monument in San Antonio, Texas that compares Suneemon to the Alamo defenders.

Nor was the brave soldier’s sacrifice in vain. The garrison did hold on — and their allies did relieve them, and did rout the Takeda in the resulting Battle of Nagashino. (The scenario is widely reproduced in video games nowadays).

* Some sites give this as “May 16”, but I believe the primary sources here actually indicate the 16th day of the 5th month on the traditional Japanese lunisolar calendar. This date corresponds to June 24, 1575 of the Julian calendar. (1570s conversion aid in this pdf, or use this converter).

On this day..

- 1958: Raymond John Bailey, for the Sundown Murders - 2020

- 1567: Captain William Blackadder, Darnley patsy - 2019

- 1931: Xiang Zhongfa, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party - 2018

- 1794: Rosalie Filleul, painter - 2017

- 1884: Field executions during the Bac Le ambush - 2016

- 1718: Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich condemned and fatally knouted - 2015

- 1340: Nicholas Behuchet, Battle of Sluys naval commander - 2014

- 1890: A quadruple hanging in Jim Crow America - 2013

- 1986: Jerome Bowden - 2011

- 1908: Two Persian constitutionalists - 2010

- 2008: Tseng Fu-wen, drug dealer - 2009

- 1953: Dmytro Bilinchuk, Company 67 of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army - 2008

The

The

On an uncertain date roughly around this time in 71 B.C.E., some 6,000 survivors of the shattered rebel slave army of

On an uncertain date roughly around this time in 71 B.C.E., some 6,000 survivors of the shattered rebel slave army of