The first “executions” meted out by Mormon captors to the Aiken or Aikin Party men who were attempting to cross the war-footing territory eastward from California took place on November 25, 1857, and were as clumsy as they were brutal.

Under the pretext of escorting them out of the state, Thomas Aiken, John Aiken, John “Colonel” Eichard, and Andrew Jackson “Honesty” Jones reached the small settlement of Salt Creek, Utah, on November 24. They had their least peaceful sleep there that night while their guides, acting on orders from the top of the state’s hierarchy, planned their murders.

Four toughs dispatched by Bishop Jacob Bigler slipped out of Nephi before dawn the next day. They’d ride on ahead, and later that evening “accidentally” meet the southbound Aiken men and their escorts, presenting themselves as a chance encounter on the trails to share a camp that night. These toughs plus the escorts gave the Mormons an 8-to-4 advantage on their prisoners, which was still only good enough to kill 2-of-4 when the time came:

David Bigler’s 2007 Western Historical Quarterly article, “The Aiken Party Executions and the Utah War, 1857-1858.”

After supper, the newcomers sat around the fire singing. “Each assassin had selected his man. At a signal from [Porter] Rockwell, [the] four men drew a bar of iron each from his sleeve and struck his victim on the head. Collett did not stun his man and was getting worsted. Rockwell fired across the camp fire and wounded the man in the back. Two escaped and got back to Salt Creek.”

We don’t actually know which two died at the camp and which two made it back to Salt Creek. Bigler suspects Thomas Aiken and John Eichard were the victims to die on the 25th; the editors of Mormon assassin Bill Hickman‘s confessional autobiography make it Thomas Aiken and Honesty Jones.

The doomed men were stopping at T. B. Foote’s, and some persons in the family afterwards testified to having heard the council that condemned them. The selected murderers, at 11 p.m., started from the Tithing House and got ahead of the Aikins, who did not start till dayhght. The latter reached the Sevier River, when Rockwell informed them they could find no other camp that day; they halted, when the other party approached and asked to camp with them, for which permission was granted. The weary men removed their arms and heavy clothing, and were soon lost in sleep — that sleep which for two of them was to have no waking on earth. All seemed fit for their damnable purpose, and yet the murderers hesitated. As near as can be determined, they still feared that all could not be done with perfect secrecy, and determined to use no firearms. With this view the escort and the party from Nephi attacked the sleeping men with clubs and the kingbolts of the wagons. Two died without a struggle.

As for the two survivors … that’s a tale for another day.

On this day..

- 1939: Manuel Molina, Valencia socialist - 2019

- Corpses Strewn: The Aiken Party Massacre - 2018

- 1679: Five Covenanter prisoners from the Battle of Bothwell Bridge - 2017

- 1944: Victor Gough, of Operation Jedburgh - 2016

- 1836: Six Creek rebels, amid removal - 2015

- 1730: Patrona Halil, Ottoman rebel - 2014

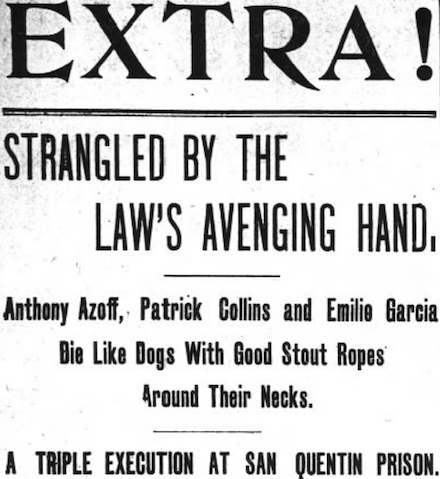

- 1881: Four Black Friday hangings - 2013

- 1977: Benigno Aquino condemned - 2012

- 1988: Adrian Lim and his two wives - 2011

- 1838: Tsali, Cherokee - 2010

- 2008: Amoudou Samassa, to quell a lynch mob - 2009

- 1780: David Dawson and Ralph Morden, Quaker "traitors" - 2008

- Feast Day of St. Catherine of the Wheel - 2007