Francisco Ruiz, the carpenter of the Spanish piratical schooner Panda, who was distinguished above his brother buccaneers, by his pre-eminence in guilt, and violence, in the robbery of the Mexican, and yet had succeeded outliving them a few months, and prolonging a miserable existence in jail, by counterfeiting madness, in which, however, there was altogether too much method, was executed on Saturday morning in the jail yard.

At the trial of the Pirates, last December,* Ruiz was more positively identified than the others, on account of the prominent part which he took in the proceedings on board of the Mexican: he was pointed out as the man, who, with a drawn sword, drove the crew below, and as keeping guard over the hatchway while the vessel was pillaged of her specie; he was also singled out by the steward as the individual who beat him with a baton to compel him to disclose where he had secreted his private property.

Under his direction the sails were slashed, the combustables collected in the camboose, and the arrangements completed, for the setting fire to the sails and rigging of the plundered brig, which was happily arrested by her crew who escaped from below, by an aperture, which the pirates, in their haste to abandon her, fortunately omitted to secure.

Had the crew remained below an other [sic] minute, the brig would have been enveloped in one general conflagration, and not a man could have survived to recount the fate of his vessel and companions.

In the river Nazareth too, when the Panda, closely pressed by the British boats, was abandoned by her officers and crew, to Ruiz was assigned the dangerous duty of securing the ship’s papers, and then blowing her up, but his attempt to explode her magazine proved as unsuccessful as his infernal endeavor to wrap the Mexican in flames, in the middle of the ocean.

Since the expiration of Ruiz’s second respite, Mr. Marshall Sibley had procured the attendance, at the jail, of two experienced physicians, belonging to the U.S. Service, and who, being acquainted, with the Spanish language, were able to converse freely with him.

They had continued access to him, during the past month, and, as the result of their observations, reported to the Marshall in writing, that they had visited Ruiz several times for the purpose of ascertaining whether he was, or was not insane; and from their opportunities of observing him, they expressed their belief, that he was not insane.

This opinion being corroborated by other physicians, unacquainted with the Spanish language, but judging only from Ruiz’s conduct, induced the Marshal to forbear urging the Executive for a further respite; and for the first time, on Saturday morning, in an interview with the Spanish Interpreter and Priest, he was made sensible, that longer evasion of the sentence of the law was impracticable, and that he must surely die.

They informed him, that he had but half an hour to live, and retired, when he requested that he might not be disturbed during the brief space that remained to him, and turning his back to the open entrance of his cell, he unrolled some fragments of printed prayers, and commenced reading them to himself.

During this interval he neither spoke, nor heeded those who were watching him; but undoubtedly sufferred ]sic] extreme mental agony. At one minute he would [obscure] his chin on his bosom, and stand motionless; at another he would press his brow to the wall of his cell, or wave his body from side to side, as if wrung with unutterable anguish.

Suddenly, he would throw himself upon his knees on his mattress, and prostrate himself on his face as if in prayer; then throwing his prayers from him, he would clutch his rug in his fingers, and like a child try to double it up, or pick it to pieces.

After snatching up his rug and throwing it away again and again, he would suddenly resume his prayers, and erect posture, and stand mute, gazing through the aperture that admitted the light of day, for upwards of a minute.

This scene of imbecility and indecision — of horrible prostration of mind — eased in some degree when the Catholic clergyman re-entered his cell.

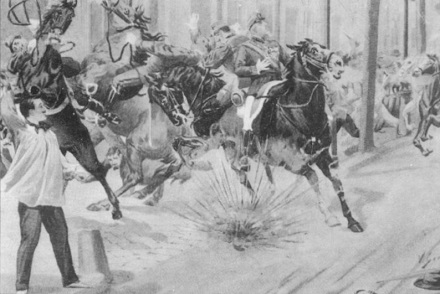

Precisely at 10 o’clock, the prisoner was removed from the prison, and, during his process to the scaffold, though the palor of death was spread over his countenance, and he trembled n every joint with fear, he chanted with a powerful voice an appropriate service from the Catholic ritual.

Several times he turned half round to survey the heavens, which at that moment were clear and bright above him, and when he ascended the platform, after concluding his last audible prayer, he took one long and steadfast gaze at the sun, and waited, in silence, his fate.

Unlike his comrades who had preceded him, he uttered no exclamations of innocence — his mind never appeared to revert to his crime.

His powers, mental and physical, had been suddenly crushed with the appalling reality that surrounded him; his whole soul was absorbed with one master feeling — the dread of a speedy and violent death.

Misunderstanding the lenity of the government, and the humanity of the officers, he had deluded himself with the hope of eluding his fate, and not having steeled his heart for the trying ordeal, it quailed in the presence of the dreadful paraphernalia of his punishment, as much as if he had been a stranger to deeds of blood, and never dealt death to his fellow man, as he ploughed the deep under the black flag of piracy, with the motto of “Rob, Kill, and Burn.”

He appeared entirely unconscious — dead, as it were — to all that was passing around him, when Deputy Marshal Bass coolly and securely adjusted the fatal cap, and, at the Marshall’s signal, which soon followed, adroitly cut the rope, which held down the latches of the platform.

The body dropoped heavily, and the harsh, abrupt shock must have instantly deprived him of all sensation, as there was no voluntary action of the hands afterwards. The body hung motionless half a minute, when a violent spasmodic action took place, occasioned simply by muscular contraction, but confined chiefly to the trunk of the body, which seemed to draw up the lower extremities into itself. The muscles of the heart continued to act nearly half an hour, but no pulsation was perceptible in a very few minutes after the fall.

Thus terminated his career of crime, in a foreign land, without one friend to recognize or cheer him, or a single being to regret his death — dying in very truth “unwept, unhonored.”

The skull of Delgrado, the suicide, who held the knife to Capt. Butman’s throat, was thought by the phrenologists to favor their supposed science; but they will find in the head of Ruiz a still more extraordinary development of the destructive, and other animal propensities, if we were not deceived in the alleged localities of these organs.

The execution took place in one of the most secluded situations in the City — not a hundred persons could witness it from within the yard; and very few, excepting professional persons, having business there, and the officers, were admitted inside.

Great credit is due to the U.S. Marshall for the privacy with which he caused the execution to be performed, and for not interrupting, by exhibiting a public, and exciting through barbarous spectacle, the business of the community.

* The long interval which has elapsed since the conviction of Capt. Gilbert and his crew, has afforded the most ample time to bring to light facts tending to establish their innocence, if any had been in existence; and the non-production of such facts, under the circumstances, must remove every possible shadow of a doubt of their guilt.