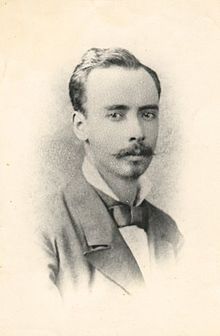

On this date in 1883, Leoncio Prado Gutierrez (English Wikipedia entry | the very much more extensive Spanish) was shot by the Chileans during the War of the Pacific.

Prado’s father, Manuel Ignacio Prado, was twice the president of Peru (1865-1868,* 1876-1879).

Prado’s father, Manuel Ignacio Prado, was twice the president of Peru (1865-1868,* 1876-1879).

As a military man (Prado’s first presidency was as outright dictator), the old man naturally had his son on a soldierly track as well. Leoncio was all of 12 years old when he took part in the Battle of Callao in 1866, defending that city against a Spanish bombardment during the Chincha Islands War.

That war saw Peru and Chile cooperating against Spain, after the latter seized a lucrative cluster of guano islands.

But different resource rivalries put the two former allies at loggerheads in 1879. When Peru nationalized saltpeter mining in the border province of Tarapaca — dispossessing Chilean interests — and Bolivia took similar measures, the countries fought the three-way War of the Pacific, also known as the Saltpeter War.

Chile would win the war decisively, dramatically reshaping Latin America in the process. Peru lost most of Tarapaca to Chile, devastating Peru’s saltpeter industry and provoking a generation of instability and social crisis. Bolivia fared even worse, losing its only littoral province to Chile: Bolivia remains landlocked to this day.

So it’s safe to say that there was something at stake worth fighting for as hostilities commenced.

By this time Leoncio Prado was 26, and a veteran of the intervening years’ Cuban war for independence from Spain.

As the Saltpeter War got underway, Prado returned from the United States where he was preparing an expedition to help Philippines separatists, and formed a guerrilla force. Though this corps had its highlight moments, it was overwhelmed in a scrap with Chilean regulars in July 1880 and Prado taken prisoner.

Considering his lineage and his exploits, he was an honored captive for the Chileans who repeatedly offered to release him on his honor not to take up arms again.

Prado refused these offers for some time, but he finally accepted his parole at the start of 1882 — a low ebb for Peruvian fortunes, for his father had been deposed by a coup and 1881-82 saw leadership of the country violently contested. Prado’s only thought, notwithstanding his pledge to Chile, was for the defense of his country and he rallied another party of guerrillas to his banner. “The enemy’s bullets do not kill,” he cried. “For to die for the fatherland is to live in immortal glory!”

That has proved to be the case for Prado, who certainly stood out from the politicians of his time for his patriotic heroism.

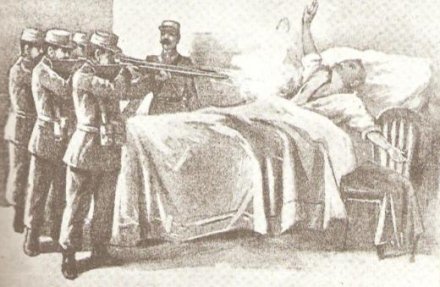

Captured during the decisive Chilean victory at the Battle of Huamachuco where a grenade shattered his thigh, the crippled Prado was regretfully executed in his bed for having broken his previous parole by resuming arms in the fight.

“We were all crying — all but Pradito,” recalled the Chilean captain tasked with overseeing the nasty business.

Six years after Prado’s execution, his aged father — the ex-president — sired yet another son, Manuel Prado Ugarteche. That son would also go on to hold the Peruvian presidency. While in office, he christened the Leoncio Prado Military Academy, an institution distinguished in literature as the setting for the Mario Vargas Llosa novel The Time of the Hero

* Prado pere was ousted from his first turn at the helm of state — a dictatorship — by Jose Balta, whose sad fate has adorned these macabre pages.

On this day..

- 1942: Wenceslao Vinzons

- 1958: Nuri al-Said

- 1857: Danforth Hartson, again

- 1738: Baruch Leibov and Alexander Voznitsyn, Jew and convert

- 1381: John Ball, radical priest

- 1936: Charlotte Bryant

- 756: Yang Guifei, favored concubine

- 1927: Three persistent escapees

- 1907: Qiu Jin, Chinese feminist and revolutionary

- 1953: John Christie, a little late in the day

- 1977: Princess Misha'al bint Fahd al Saud and her lover

- Themed Set: The Feminine Mystique

- 1685: James Scott, Duke of Monmouth

Soon Alice’s sister-in-law dropped the pretense of punishment and simply hit Alice whenever she felt like it. Emeline was quite literally deaf to the little girl’s screams, as she had a severe hearing impairment. So did Horace.

Soon Alice’s sister-in-law dropped the pretense of punishment and simply hit Alice whenever she felt like it. Emeline was quite literally deaf to the little girl’s screams, as she had a severe hearing impairment. So did Horace. “He was brought up as a stonemason,” the May 15, 1883 London Times recalled of the by-then-hanged man, “of herculean strength, his occupation developing the muscular power of his arms, which told with such terrible effect when he drove the knives into the bodies of his victims.”

“He was brought up as a stonemason,” the May 15, 1883 London Times recalled of the by-then-hanged man, “of herculean strength, his occupation developing the muscular power of his arms, which told with such terrible effect when he drove the knives into the bodies of his victims.”