(Thanks to Meaghan Good of the Charley Project for the guest post. -ed.)

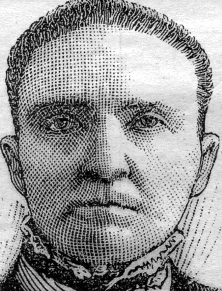

On this day in 1883, Emeline Lucy Meaker was hanged for the murder of her nine-year-old sister-in-law and ward, Alice. She was the first woman executed in Vermont and almost the last; the only other one was in 1905, when Mary Mabel Rogers was hanged after killing her husband for his insurance.

Alice’s father died in 1873 and her impoverished mother sent her and her brother Henry to live in an overcrowded poorhouse. There, the little girl was reportedly sexually abused. Others noted that she was “a timid, shrinking child—of just that disposition that seems to invite, and is unable to resist—persecution.”

In 1879, Alice and Henry got a chance for a better life when their much older half-brother* Horace (described by crime historian Harold Schechter as a “perpetually down-at-heels farmer”) agreed to take them in for a lump sum of $400. However, Horace’s wife, Emeline, was unhappy at this extra burden. She referred to Alice as “little bitch” and “that thing.”

Schechter writes of the killer in his book Psycho USA: Famous American Killers You Never Heard Of:

Married to Horace when she was eighteen, forty-five-year-old Emeline was (according to newspapers at the time) a “coarse, brutal, domineering woman,” a “perfect virago,” a “sullen, morose, repulsive-looking creature.” To be sure, these characterizations were deeply colored by the horror provoked by her crime. Still, there is little doubt that … Emeline’s grim, hardscrabble life had left her deeply embittered and seething with suppressed rage — “malignant passions” (in the words of one contemporary) that would vent themselves against her helpless [sister-in-law].

Young Alice’s life, however difficult it may have been before, became hell after she went to live with her half-brother and his family.

She was forced to do more and heavier chores than she was capable of, and for the slightest reason, Emeline would beat her horribly with a broom, a stick or whatever else was at hand.

Soon Alice’s sister-in-law dropped the pretense of punishment and simply hit Alice whenever she felt like it. Emeline was quite literally deaf to the little girl’s screams, as she had a severe hearing impairment. So did Horace.

Soon Alice’s sister-in-law dropped the pretense of punishment and simply hit Alice whenever she felt like it. Emeline was quite literally deaf to the little girl’s screams, as she had a severe hearing impairment. So did Horace.

Some of the neighbors later said they could hear the child’s cries from half a mile away, and Emeline had no compunctions about abusing Alice in front of visitors. Everyone in in their small community of Duxbury was aware of what was going on, but no one bothered to do anything about it until it was too late.

Less than a year after Alice’s arrival, Emeline decided to do away with her. The crime is reported in detail in Volume 16 of the Duxbury Historical Society’s newsletter.

Emeline convinced her twenty-year-old “weak minded” and “not over bright” son, Lewis Almon Meaker, to help. He later said his mother had persuaded him that Alice would be “better off dead” and that “she wasn’t a very good girl; no one liked her.”

Emeline’s first suggestion was to take Alice out into the mountain wilderness and leave her there to die, but Almon thought this was too risky. Instead, on the night of April 23, 1880, Almon and Emeline woke up Alice, shoved a sack over her head and carried her to the carriage Almon had hired in advance. They drove to a remote hill and forced Alice to drink strychnine from her own favorite mug, which her mother had given her.

Twenty minutes later, the child’s death agonies ceased and Almon buried her in a thicket outside the town of Stowe.

Emeline and Almon, people who had been concerned about the riskiness of a previous murder plot, didn’t bother to get their stories straight about the unannounced disappearance of their charge, so when the neighbors asked where Alice had gone their contradictory explanations for her disappearance raised suspicions.

On April 26, a police officer subjected both mother and son to questioning. Almon didn’t last long before he broke down and confessed. He led the deputy sheriff to the burial site and they disinterred Alice’s remains, still visibly bruised from her last thrashing. Because the deputy’s buggy was small, Almon had to hold Alice’s corpse upright to keep it from falling out during the three-hour journey back to Roxbury.

That must have been some ride.

Emeline and Almon were both charged with murder. Each defendant tried to put as much blame as possible on the other, but both were ultimately convicted and sentenced to death. Almon’s sentence was commuted to life in prison, but Emeline’s was upheld in spite of years of appeals and a try at feigning madness.

Her violent tantrums, attempts at arson, and attacks on the prison staff didn’t convince anyone she was crazy — they merely alienated her family and others who might have otherwise supported her. Once she realized she wasn’t fooling anybody, she calmed down and passed her remaining days quietly knitting in her cell.

She was hanged at 1:30 p.m., 35 months after the murder.

On the day of her execution she asked to see the gallows. The sheriff explained to her how it worked and she declared, “Why, it’s not half as bad as I thought.” For the occasion — she had a crowd of 125 witnesses to impress — she wore a black cambric with white ruffles.

The not-half-bad gallows snapped Emeline Meaker’s neck, but it still took her twelve minutes to die. Emeline wanted her body returned to her husband, but Horace refused to accept it and it was buried in the prison cemetery.

Ten years after his mother’s execution, Almon died in prison of tuberculosis.

* Some reports say Alice was Horace’s niece rather than his half-sister.

On this day..

- 1908: Chester Gillette, A Place in the Sun inspiration

- 2007: Six Bangladesh bombers

- 1900: Joseph Hurst

- 1702: Not Nicholas Bayard, anti-Leislerian

- 1781: Diego Corrientes Mateos, Spanish social bandit

- 1555: Robert Ferrar, Bishop of St. David's

- 1875: John Morgan, slasher

- 1911: Joseph Christock

- 2011: Three Philippines drug mules in China

- 1938: Arkadi Berdichevsky, Jon Utley's father

- 1952: Nikos Beloyannis, the man with the carnation

- 1689: Kazimierz Lyszczynski, the first Polish atheist

Pingback: Burial Insurance In Morgan Vermont – Cheap Burial Insurance Plans for Seniors

Emeline doesn’t have a tomb/crucifix in the VT State Prison Cemetery however Almon does.