On this date in 1790, Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras, became a penal milestone: the first French noble executed without class distinction from commoners.

At least he made history.

The scion of an ancient and penurious noble line, Favras was trying to make a different kind of history: he’d hitched onto a plot of the future Louis XVIII to reverse the still-infant French Revolution and rescue the king and queen from captivity in the Tuileries.

The royal couple were ultimately destined to escape this palatial dungeon only to the guillotine.

But in Mahy’s day, it was possible to dream of counterrevolution. And that terrifying machine of the revolution hadn’t even been invented.

For that matter, the machinery of revolutionary justice had also not been born; this was Lafayette‘s year, the revolution in its moderate phase.

It was ancien regime jurists of the Chatelet who were here appointed to judge the enemies of the nation. Having just acquitted the guy who commanded monarchist forces in Paris on Bastille Day, these establishment magistrates proceeded to throw the revolutionary left a bone by condemning Favras to the democratic capital expiration of … hanging. (Back in the good old days, he would have had the right to a beheading. Plus ça change.)

The crowd was said to be quite enthusiastic.

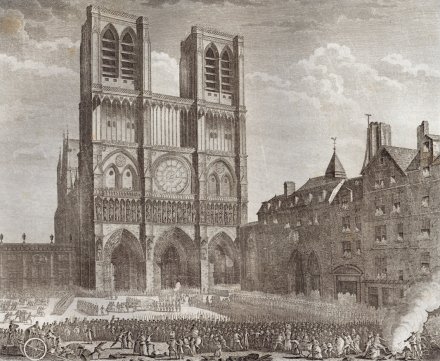

“Thomas de Mahy, Marquis of Favras Making Honourable Amends before Notre-Dame,” engraving by Pierre-Gabriel Berthault (French link).

Little less interested in Favras’s elimination — he was executed the day after sentence — were his fellow conspirators and other sympathetic members of the royalist party. (Future-Louis XVIII hurriedly washed his hands of the scheme.) These were quite pleased to suppress any wider exploration of

the project that this lost child of royalist enthusiasm had formed in the interest of the royal family. Among those participating in this project, but with a cowardice that is well known, were persons that an important consideration prevented from naming at the time.*

You’ve got to look forward, not back.

Despite the mob scene surrounding him as he carried his damning information to the grave, Favras had the sang-froid to remark upon being handed a copy of the order for his execution, “I see that you have made three spelling mistakes.”

“It can be said,” wrote Camille Desmoulins, “that all the aristocrats have been hung through him.”

And since they did such a metaphorically comprehensive job through this single unfortunate, it’s no wonder that Favras was the only aristocrat executed for counterrevolutionary activity during the entire first three years of the Revolution.*

* Barry Shapiro, “Revolutionary Justice in 1789-1790: The Comité des Recherches, the Châtelet, and the Fayettist Coalition,” French Historical Studies, Spring 1992.

On this day..

- 1803: Mathias Weber, Rhineland robber - 2020

- 1901: Sampson Silas Salmon - 2019

- 1951: Jean Lee, the last woman to hang in Australia - 2018

- 1329: The effigy of Pope John XXII, by Antipope Nicholas V - 2017

- 2009: Abdullah Fareivar, by the rope instead of the stone - 2016

- 1861: The Bascom Affair hangings, Apache War triggers - 2015

- 1878: J.W. Rover, sulfurous - 2014

- 1762: Francois Rochette and the Grenier brothes, the last Huguenot martyrs in France - 2013

- 1836: Giuseppe Fieschi, Pierre Morey, and Theodore Pepin, infernal machinists - 2012

- 1388: Robert Tresilian, former Chief Justice - 2010

- Daily Double: The Merciless Parliament - 2010

- 1858: Chief Leschi - 2009

- 1942: Frank Abbandando and Harry Maione, mob hitmen - 2008