On this date in 1951, the first of two batches comprising the “Martinsville Seven” — black, all — went to the Virginia electric chair for gang-raping a white woman. (The remainder were executed on Feb. 5)

Somewhat forgotten today, the Martinsville Seven were in their day the locus of radical activism against Jim Crow in the South — very much like Willie McGee, who was put to death in Louisiana later that same year.

In fact, this case generated a bit of a legal milestone: a month before the executions began, the U.S. Supreme Court declined an appeal seeking relief on the then-novel grounds of equal protection — rather than due process.

The argument was that the Old Dominion’s superficially race-neutral rape statute was anything but; that argument was buttressed by data showing that Virginia had executed 45 black men for raping white women from 1908 to 1950, but never once in that period executed any white man for raping a black woman. (The high court only declined to take the appeal; it wouldn’t get around to explicitly ruling equal protection claims based on racial patterns out of bounds until 1987’s McCleskey v. Kemp.)

This seems to be the debut use for this gambit, bound to become an increasingly powerful one both in and out of the courtroom during the civil rights movement.

And it was available — and necessary — here because the Martinsville Seven basically looked guilty as sin. Their confessions and the victim’s accusation and the testimony of a young eyewitness said that, drink-addled, they had opportunistically grabbed a white Jehovah’s Witness housewife when she was proselytizing on the wrong side of the tracks.

Eric Rise, author of The Martinsville Seven: Race, Rape, and Capital Punishment, noted in a scholarly article,*

certain striking characteristics distinguished the proceedings from classic “legal lynchings.” The evidence presented at trial clearly proved that nonconsensual sexual intercourse with the victim had taken place. All seven defendants admitted their presence at the scene, and although some of the men may not have actually consummated the act … The prosecution emphasized the preservation of community stability, not the protection of southern womanly virtues, as the dominant concern of Martinsville’s white citizens. Most significant, the trial judge made a concerted effort to mute the racial overtones of the trials. Although white juries decided each case, blacks appeared in every jury pool. Race-baiting by prosecutors and witnesses, notably evident at Scottsboro and other similar trials, was absent from the Martinsville proceedings. By diligently adhering to procedural requirements, the court attempted to try the case “as though both parties were members of the same race.”**

The standard playbook for fighting a “legal lynching” case was leveraging outrage over a plausibly innocent convict and an outrageous kangaroo court.†

Paradoxically, by taking these elements out of the mix (relatively speaking), the Martinsville Seven perfectly isolated the extreme harshness of the penalty and the structural discrimination under which it was imposed. The NAACP took up the case on appeal strictly for its discriminatory characteristics, steering for its part completely clear of any “actual innocence” argument.

These challenges posed discomfiting questions that jurists shrank away from. The Virginia Supreme Court, in denying an equal protection application, fretted that actual legal relief could mean that “no Negroes could be executed unless a certain number of white people” were, too. Timeless.

Though a later U.S. Supreme Court would completely overturn death-sentencing for rape, based in part on its overwhelming racial slant, justices have generally avoided meddling to redress broad statistical patterns rather than identifiable process violations specific to particular cases.

Those questions of substantive — rather than merely procedural — equality in the justice system remain potently unresolved, still part of Americans’ lived experience of the law from death row to the drug war to driving while black. As if to underscore the point in this instance, just two days prior to the first Martinsville executions, the Wall Street bankster acting as American proconsul in conquered Germany pardoned imprisoned Nazi industrialist Alfried Krupp, and restored him to the fortune he had amassed working Jewish slaves to death during the war. It was a very particular quality of mercy the U.S. showed the world in those days. (The Martinsville case was known, and protested, worldwide.)

Carol Steiker (she used to clerk for liberal Justice Thurgood Marshall, who as an NAACP lawyer worked on the Martinsville case) argues‡ that the Martinsville Seven’s legacy is linked to their later obscurity, for “[t]heir attempt to present statistical proof of discrimination in capital sentencing represents a ‘road not taken'” — neither in 1951, nor since.

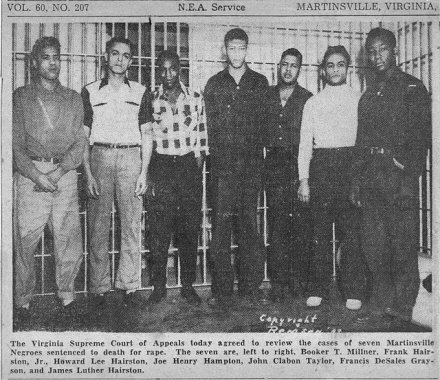

The road taken instead had Joe Henry Hampton, 22, Howard Hairston, 21, Booker Millner, 22 and Frank Hairston, 19 electrocuted one by one this morning in 1951. Their three co-accused, John Clabon Taylor, 24, James Luther Hairston, 23, and Francis DeSales Grayson, 40, followed them on February 5.

* “Race, Rape, and Radicalism: The Case of the Martinsville Seven, 1949-1951” in The Journal of Southern History, Aug., 1992.

** This quote an actual trial admonishment of the judge, Kennon Whittle.

† Graded on a curve: this is still Jim Crow Virginia. Six trials were wrapped up at warp speed in 11 days, with a total of 72 jurors — each one white. The implied comparison is something along the lines of, all seven tried together in the course of an afternoon, with a good ol’ boy defense attorney mailing it in.

‡ Review of Rise’s book titled “Remembering Race, Rape, and Capital Punishment” in the Virginia Law Review, Apr., 1997

On this day..

- Feast Day of St. Apronian the Executioner - 2020

- 1610: Pierre Canal, Geneva sodomite - 2019

- 1715: Ann Wright, branded - 2018

- 1637: Tabaniyassi Mehmed Pasha, former Grand Vizier - 2017

- 1940: Mikhail Koltsov, Soviet journalist - 2016

- 1905: Elisabeth Wiese, the angel-maker of St. Pauli - 2015

- 1989: Vladimir Lulek, the last Czech executed - 2014

- 1708: Indian Sam and his female accomplice - 2013

- 1945: Carl Goerdeler, as penance for the German people - 2011

- Daily Double: 1945, and the legacy of Valkyrie - 2011

- 1461: Owen Tudor, sire of sires - 2010

- 1940: Vsevolod Meyerhold - 2009

- 1512: Hatuey, defied Spanish colonization - 2008