(Thanks to Anthony Vaver of Early American Crime for the guest entry, reposted from a fascinating entry in his series on convict transportation. Vaver is the author of Bound With An Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America. -ed.)

Mary Standford was convicted of privately stealing a shagreen pocket book, a silk handkerchief, and 4 guineas from William Smith on July 11, 1726. After her conviction, she strongly rejected transportation to the American colonies as an alternative to execution.

Early Years

Standford was raised just outside of London by good parents who sent her to school and educated her in the principles of Christian values. Standford, however, showed more interest in the “Company of Young Men,” so she was sent to London to become a servant, where she lost several positions due to her behavior. In her last position she was seduced by a footman, which subsequently forced her into prostitution.

Standford quickly fell in company with Mary Rawlins, “a Woman of notorious ill fame,” and the two of them walked the streets between Temple Bar and Ludgate-Hill looking to empty the pockets, one way or another, of gullible men. Later, they had considerable success targeting sailors who, after returning from their voyages, had money to spend for their favors. Standford eventually married a man with the last name of Herbert, but after a year and a half she left him or, by her account, he abandoned her. Soon afterward, she had a child out of wedlock from another man, who was a servant.

Standford’s Arrest

With two mouths to feed, Standford set out to practice prostitution on her own, and it was then that she was arrested for theft. William Smith, who brought her to trial and was surprisingly frank in his testimony, related that he was walking along Shoe Lane after one o’clock in the morning when he was approached by Standford, who offered him to “take a Lodging with her.” He spent 2 or 3 three hours with her, all the while ordering drinks to be brought up from downstairs. He soon realized that he was missing money, and when he confronted Standford about it, she bolted from the room.

A constable caught Standford running away from Smith in the street. He picked up one of Smith’s guineas after Standford had dropped it, and he found another in her hand and two in her mouth. He also discovered Smith’s handkerchief and pocket book on her. In his testimony, the constable called Smith a “Country Man” and described him as very drunk at the time.

Standford’s version of the event was quite different. She claimed that Smith was drunk when she met him, and that he forced himself up to her room. There, he placed the four guineas one by one in her bosom and then threw her onto the bed. In the struggle, she speculated that his pocket book must have fallen out of his pocket, and when she discovered it after he left, she ran after him to return it. Not believing her story, the jury found her guilty, and she was sentenced to death.

A Rejection and a Defense of Transportation

After receiving her sentence, Standford’s friends pleaded with her to ask for a pardon in exchange for transportation. Standford refused, “declaring that she had rather die, not only the most Ignominious, but the most cruel Death that could be invented at home, rather than be sent Abroad to slave for her Living.”

The author of the Lives of the Most Remarkable Criminals was baffled by Standford’s position and presents a lengthy defense of the institution of convict transportation:

such strange Apprehensions enter into the Heads of these unhappy Creatures, and hinder them from taking the Advantage of the only possibility they have left of tasting Happiness on this side the Grave, and as this Aversion to the Plantations has so bad Effects, especially in making the Convicts desirous of escaping from the Vessel, or of flying out of the Country whither they were sent, almost before they have seen it. I am surpriz’d that no Care has been taken to print a particular and authentick Account, of the Manner in which they are treated in those Places; I know it may be suggested that the Terrour of such Usage as they are represented to meet with there, has often a good Effect in diverting them from such Facts as they know must bring them to Transportation, yet . . . if instead of magnifying the Miseries of their pretended Slavery, or rather of inventing Stories that make a very easy service, pass on these unhappy Creatures for the severest Bondage. The Convicts were to be told the true state of the Case, and were put in Mind that instead of suffering Death, the Lenity of our Constitution, permitted them to be removed into another Climate, no way inferiour to that in which they were born, where they were to perform no harder tasks, than those who work honestly for their Bread in England do, and this not under Persons of another Nation, who might treat them with less Humanity upon that Account, but to their Countrymen, who are no less English for their living in the New, than if they dwelt in Old England, People famous for their Humanity, Justice and Piety, and amongst whom they are sure of meeting with no variation of Manners, Customs, &c. unless in respect of the Progress of their Vices which are at present, and may they long remain so, far less numerous there than in their Mother-Land. I say if Pains were taken to instill into these unhappy Persons such Notions . . ., they might probably conceive justly of that Clemency which is extended towards them, and instead of shunning Transportation, flying from the Countries where they are landed, as soon as they have set their Foot in them, or neglecting Opportunities they might have on their first coming there, be brought to serve their Masters faithfully, to endure the Time of their Service chearfully, and settle afterwards in the best Manner they are able, so as to pass the Close of their Life in an honest, easy, and reputable Manner; whereas now it too often happens, that their last End is worse than their first, because those who return from Transportation being sure of Death if apprehended, are led thereby to behave themselves worse and more cruelly than any Malefactors whatsoever (Vol. III, pp. 287-289).

The author’s cheery account of life as an indentured servant in the American colonies certainly makes transportation sound like a compelling alternative to execution. The reality of life overseas under such conditions, though, does not match this picture, and some criminals valued their liberty over enforced servitude, even if it meant their own death.

Execution

In his account of her execution, James Guthrie, the minister at Newgate Prison, described Standford as “grosly Ignorant of any thing that is good.” He went on to say that “she was neither ingenious nor full in her Confessions, but appeared obstinate and self-conceited.” Standford continued to maintain her innocence in the affair with Smith, and she appeared indifferent about the fate of her child, expressing to Guthrie the hope that the parish would take care of it. Guthrie claimed, however, that “she acknowledg’d herself among the chief of Sinners.”

Mary Standford was executed on Wednesday, August 3, 1726 at Tyburn. She was 36 years old. Executed alongside her were 3 other criminals. Thomas Smith and Edward Reynolds were both sentenced to die for highway robbery. John Claxton, alias Johnson, was put death for returning twice from transportation before his 7-year sentence had run out.

Resources for this article:

- Lives of the Most Remarkable Criminals. 3 vols. London: John Osborn, 1735.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, 26 January 2009), July 1726, trial of Mary Stanford (t17260711-51).

- Old Bailey Proceedings (www.oldbaileyonline.org, 26 January 2009), Ordinary of Newgate’s Account, 3 August 1726 (OA17260803).

On this day..

- 1928: Jim Moss, former Negro League ballplayer - 2020

- 1151: Konrad von Freistritz, ruined - 2019

- 1599: Elisabeth Strupp, Gelnhausen witch - 2018

- 1829: John Stacey, in Portsmouth town - 2017

- 1546: Etienne Dolet, no longer anything at all - 2016

- 1795: Jerry Avershaw, contemptuously - 2015

- 1530: Francesco Ferruccio, victim of Maramaldo - 2014

- 1949: Jacob Bokai, the first Israeli spy executed - 2013

- 1788: Not Jean Louschart, rescued by the crowd - 2012

- 1573: William Kirkcaldy of Grange, former king's man - 2011

- 1976: Valery Sablin, Hunt for Red October inspiration - 2010

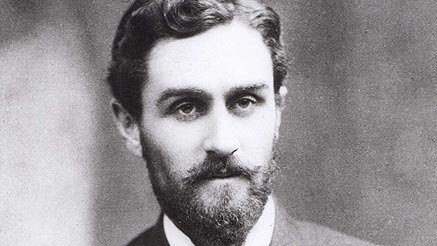

- 1916: Sir Roger Casement - 2008