(Thanks to the Communist historian C.L.R. James for this guest post, an excerpt of his classic exploration of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins. James here details a pivotal incident in the last months of the ascendancy of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the great general of the Haitian Revolution, when his militant adoptive nephew Hyacinth Moise joined a rebellion of plantation workers — former slaves — against the harsh discipline that L’Ouverture was now re-imposing upon them. Although L’Ouverture squelched the rebellion and had Moise executed on November 9, 1801, his uncertain hold on the loyalty of his people left him vulnerable, and within months an expedition from Haiti’s former colonial overlord, France, defeated the Haitians and weighed L’Ouverture with chains. The latter died in 1803, imprisoned in a French fortress. -ed.)

And in these last crucial months, Toussaint, fully aware of Bonaparte’s preparations, was busy sawing off the branch on which he sat.

In the North, around Plaisance, Limbe, Dondon, the vanguard of the revolution was not satisfied with the new regime. Toussaint’s discipline was hard, but it was infinitely better than the old slavery. What these old revolutionary blacks objected to was working for their white masters. Moise was the Commandant of the North Province, and Moise sympathised with the blacks. Work, yes, but not for whites. “Whatever my old uncle may do, I cannot bring myself to be the executioner of my colour. It is always in the interests of the metropolis that he scolds me; but these interests are those of the whites, and I shall only love them when they have given me back the eye that they made me lose in battle.”

Gone were the days when Toussaint would leave the front and ride through the night to enquire into the grievances of the labourers, and, though protecting the whites, make the labourers see that he was their leader.

Revolutionaries through and through, those bold men, own brothers of the Cordeliers in Paris and the Vyborg workers in Petrograd, organised another insurrection. Their aim was to massacre the whites, overthrow Toussaint’s government and, some hoped, put Moise in his place. Every observer, and Toussaint himself, thought that the labourers were following him because of his past services and his unquestioned superiority. This insurrection proved that they were following him because he represented that complete emancipation from their former degradation which was their chief goal. As soon as they saw that he was no longer going to this end, they were ready to throw him over.

This was no mere riot of a few discontented or lazy blacks. It was widespread over the North. The revolutionaries chose a time when Toussaint was away at Petite-Riviere attending the wedding of Dessalines. The movement should have begun in Le Cap on September 21st, but Christophe heard of it just in time to check the first outbursts in various quarters of the town. On the 22nd and 23rd the revolt burst in the revolutionary districts of Marmelade, Plaisance, Limbe, Port Margot, and Dondon, home of the famous regiment of the sansculottes. On the morning of the 23rd it broke out again in Le Cap, while armed bands, killing all the whites whom they met on the way, appeared in the suburbs to make contact with those in the town. While Christophe defeated these, Toussaint and Dessalines marched against the rising in Marmelade and Dondon, and it fell to pieces before him and his terrible lieutenant. Moise, avoiding a meeting with Toussaint, attacked and defeated another band. But blacks in certain districts had revolted to the cry of “Long Live Moise!” Toussaint therefore had him arrested, and would not allow the military tribunal even to hear him. The documents, he said, were enough. “I flatter myself that the Commissioners will not delay a judgment so necessary to the tranquility of the colony.” He was afraid that Moise might supplant him.

Upon this hint the Commission gave judgment, and Moise was shot. He died as he had lived. He stood before the place of execution in the presence of the troops of the garrison, and in a firm voice gave the word to the firing squad: “Fire, my friends, fire.”

What exactly did Moise stand for? We shall never know. Forty years after his death Madiou, the Haitian historian, gave an outline of Moise’s programme, whose authenticity, however, has been questioned. Toussaint refused to break up the large estates. Moise wanted small grants of land for junior officers and even the rank-and-file. Toussaint favoured the whites against the Mulattoes. Moise sought to build an alliance between the blacks and the Mulattoes against the French. It is certain that he had a strong sympathy for the labourers and hated the old slave-owners. But he was not anti-white. He bitterly regretted the indignities to which he had been forced to submit Roume and we know how highly he esteemed Sonthonax. We have very little to go on but he seems to have been a singularly attractive and possibly profound person. The old slave-owners hated him and they pressed Toussaint to get rid of him. Christophe too was jealous of Moise and Christophe loved white society. Guilty or not guilty of treason, Moise had too many enemies to escape the implications of the “Long Live Moise” shouted by the revolutionaries.

To the blacks of the North, already angry at Toussaint’s policy, the execution of Moise was the final disillusionment. They could not understand it. As was (and is) inevitable, they thought in terms of colour. After Toussaint himself, Moise, his nephew, symbolised the revolution. He it was who had led the labourers against Hedouville. He also had led the insurrection which extorted the authority from Roume t take over Spanish San Domingo, an insurrection which to the labourers had been for the purpose of stopping the Spanish traffic in slaves. Moise had arrested Roume, and later Vincent. And now Toussaint had shot him, for taking the part of the blacks against the whites.

Toussaint recognised his error. If the break with the French and Vincent had shaken him from his usual calm in their last interview, it was nothing to the remorse which moved him after the execution of Moise. None who knew him had ever seen him so agitated. He tried to explain it away in a long proclamation: Moise was the soul of the insurrection; Moise was a young man of loose habits. It was useless. Moise had stood to high in his councils for too long.

On this day..

- 1716: Maria of Curacao, slave rebel

- 1773: Eva Faschaunerin, the last tortured in Austria

- 1641: Maren Splids, Jutland witch

- 1940: Julian Zugazagoitia, Minister of the Interior to republican Spain

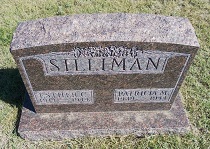

- 1945: Charles Ford Silliman, suicide pact?

- 2011: Luo Yaping, "land granny"

- 1942: Eddie Leonski, the Brownout Strangler

- 1848: Robert Blum, German democrat

- 1842: Stephen Brennan, desperate bushranger

- Themed Set: Bushrangers

- 1610: Blessed George Napier

- 1944: Georges Suarez, collaborationist editor

- 2008: The Bali Bombers

- 1911: Charles Justice

A

A

Luo Yaping was head of a land sub-bureau in a district of

Luo Yaping was head of a land sub-bureau in a district of