From Illustrated Police News, Oct. 11, 1884:

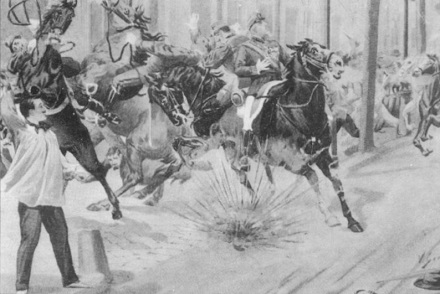

EXECUTION OF ORROCK AND HARRIS AT NEWGATE.

The two murderers, Thomas Henry Orrock and Thomas Harris, underwent the penalty of the law on Monday morning within the prison of Newgate. The circumstances of the crimes for which they suffered have been given so recently that it will not be necessary to state more than that Orrock was convicted of the murder of a police-constable named Cole, who had endeavoured to take him into custody after he had broken into a Baptist Chapel in Dalston, by shooting him with a revolver; and the other, Harris, was convicted of the murder of his wife, to whom he had been married a great many years, and who had borne him a large number of children, eleven of whom are still alive, by cutting her throat with a razor in the bedroom they occupied at Kilburn.

The first-mentioned murder was committed nearly two years ago — namely, on the 1st of Dec., 1882. The murderer got clear away, and as it was a dark, foggy night, it was generally thought to be impossible to recognise him, and the murder had nearly died away from the public mind, when, through the active exertions and inquiries made by Inspector Glasse, of the N Division of police, [including an early foray into firearm forensics -ed.] the prisoner was apprehended and his guilt of the crime was conclusively established … [he] persisted to the last in declaring that the act was not a premeditated one, and that all he was endeavouring to do was to make his escape.

The prisoner, it will be remembered, was an attendant at the chapel where the burglary was attempted, and he bore a very good reputation with the Rev. Mr. Barton, the minister of the chapel. …

His wife, who is only twenty-one years old, has been with him every day, and took a parting farewell of her unhappy husband last Saturday. At the time they were married the murder had been committed but six weeks; they were each only nineteen years old, and the bride little thought, when she clasped the hand of her husband at the marriage ceremony, that she held the hand of a murderer, almost red with the blood of his victim.

The story of the culprit’s life appears somewhat remarkable when the gravity of the offences with which he was charged are taken into consideration. Born of respectable parents in the year 1863, young Orrock was guided in the paths of virtue. His father, mother, and two sisters were regular attendants at the Baptist Chapel Ashwin-street, Dalston, the elder members of the family holding seats. In connection with the chapel is a Sunday school, which for a considerable time the youth attended. He was spoken of as a well-behaved, unassuming boy, and his general conduct was so marked as to be highly commended by the superintendent and teachers. Services of song were frequently held at the chapel, evening classes were formed, and other attractions provided, in which Orrock appeared to take delight. The pastor, the Rev. Mr. Barton, took great interest in the welfare of the youth, but unfortunately declining health caused the reverend gentleman for a time to relinquish his duties.

Between thirteen and fourteen years of age, Orrock was apprenticed to a cabinet-maker at Hoxton, and to this circumstance is attributed his downfall. The company with which he came in contact was of a dissolute class, and a short time after his apprenticeship his father had cause to reprimand him. His attendance at chapel became less frequent, and his general conduct entirely changed. About three years ago Orrock’s father died in Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. The mother being left a widow without any provision, and receiving little or no assistance from her son, after some time married again a respectable man, highly esteemed as a local preacher.

As stated at the trial Orrock, at the time of the murder, was not a constant attendant at the chapel, although at one time he held a seat. It would appear, indeed, that he was almost compelled to be present, as he was paying his addresses to a respectable young woman, who, in conjunction with her employer, frequented the chapel. She was engaged as an assistant in a draper’s shop in the locality, and, as in the case of the criminal, special interest was taken in her, she being left without father or mother. It will remembered that Orrock was actually planning the robbery whilst attending a service at the chapel, also that he was present at the funeral of his victim. When his marriage took place with the young woman alluded to six weeks had elapsed after the commission of his crime …

Orrock’s marriage did not appear to have brought about any change in his behaviour, as in the month of September, 1883, he was sentenced at the Middlesex Sessions to twelve months’ imprisonment for housebreaking and stealing a quantity of jewellery, value £20, and £45 in gold. It was while undergoing this sentence that Inspector Glasse informed him of the more serious charge he would have to answer, telling him that the information was laid by his accomplices.

When the murderer was placed in the dock of the Old Bailey his astounding self-possession attracted much notice. His appearance was that of a fresh, decent-looking young fellow, rather boyish, with a slight moustache — the last person one would expect to find in a criminal dock.

At the close of the trial, it will be remembered, Mr. Justice Hawkins expressed the greatest commiseration for the prisoner’s sister under the painful circumstances in which she was placed. In her case, as that of Orrock’s young wife, the shock of the occurrence led to premature confinement At the final parting on Saturday the wife of the convict was thoroughly broken down with grief.

With regard to the other prisoner, Harris, who is forty-eight years old, there does not appear to be any doubt that he has for a long time been in the habit of treating his unhappy partner in a most brutal manner. Upon one occasion he (the other prisoner Harris) was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment for a brutal assault upon her, and he had repeatedly threatened that he would murder her. The prisoner, however, who was a very rough, ignorant man, persisted in asserting that he was utterly unconscious of what took place on the night of the murder, and the earnest exhortations of the Rev. Mr. Duffield appeared to have very little effect upon him, or to bring him to anything like a proper sense of his condition. The only observation that could be obtained from him in reference to his crime was, “I speak the truth. I cannot say more. I know nothing about how it happened.” …

The prisoners went to bed about ten o’clock on Sunday night, Mr. Duffield having been with them alternately during the previous two hours. Orrock appeared to be quite resigned, but Harris exhibited the same callous demeanour that has characterised him since his conviction. Both prisoners got up at six o’clock on Monday morning, and very shortly afterwards they were visited by the Rev. Mr. Duffield, to whom both men expressed their gratitude for the kindness and attention shown them. Mr. Sheriff Phillips and Messrs. Crawford and Whitehead, the Under-Sheriffs, arrived at the prison about half-past seven o’clock, and were received by Captain Kirkpatrick, the Governor, who shortly afterwards accompanied them to the cells where the prisoners had been brought.

Berry, the execution, was in attendance, and the ceremony of pinioning was rapidly performed. Orrock was the first who was brought out. He walked with a firm step, was placed under the beam, and the rope put round his neck before his unhappy companion, Harris, had been placed by his side. The Rev. Mr. Duffield then read the Burial Service, and at a given signal the drop fell, a distance of seven feet five inches, and death appeared to be instantaneous, the executioner apparently having performed his work in the most skilful manner. The skin on Harris’s neck was slightly abrased, but it was stated that this was generally the case where the criminals are advanced in life, Harris being forty-eight years of age.

A considerable crowd assembled outside the prison, and it was necessary to have the attendance of two police-constables to keep the road clear.

From the Bristol Mercury, Oct. 13, 1884:

EXTRAORDINARY DEATH FROM EXCITEMENT

A death of a remarkable character, connect with the execution of the two murderers Orrock and Harris at Newgate on Monday last, has been the subject of an inquiry before the Southwark Coroner.

Eliza Kate Williamson deposed that … she was the wife of the deceased, Alexander Ben Williamson, aged 45, who was a labourer in a foundry. He came home from work on Monday night apparently quite well, and after tea sent witness for an evening newspaper in order to read the account of the executions.

She returned with a paper, and he read the account aloud, but stopped at intervals, quite overcome with emotion, and he cried several times. Witness begged him to put the paper away, saying she did not want to hear any more about it, but he would not do so, and completed the account to himself. They then went to bed, but about 1.30 a.m. the witness was awoke by a noise and found the deceased struggling by her side and trying to call out something about the execution.

She tried to rouse him, but he fell on the floor, and continued struggling and muttering after she lifted him back on the bed. He then vomited and afterwards fell into a stupor, from which he never rallied. A doctor was obtained, but death ensued about 24 hours after witness first noticed the deceased struggling.

In answer to the coroner, the witness added that the deceased was quite sober on Monday, but the execution of the two men made a great impression on him. He had read all about them in a Sunday edition of a newspaper, and frequently talked about the condemned men.

Mr. Alfred Matcham, parish surgeon, deposed that death was due to apoplexy, which he had no doubt was brought on by the excitement consequent on reading and dwelling upon the details of the executions on Monday. The struggling probably arose from dreaming of the execution, and the excitement of the dream had no doubt caused a blood vessel to burst in the brain. The jury returned a verdict of “Death from natural causes.”

On this day..

- 1960: Tibur Mikulich, Hungarian traitor

- 1750: Maria Pauer, the last witch executed in Austria

- 1909: Martha Rendell

- 1893: Paulino Pallas, Spanish anarchist

- 1918: Private Harry James Knight, deserter

- 1573: Maeykens Wens, Antwerp Anabaptist

- 1922: Benny Swim, "dead as a door-nail" (or not)

- 1943: Yitskhok Rudahevski and family

- 1646: Zhu Yujian, the Prince of Tang

- 1999: Chen Chin-hsing, Taiwan's most notorious criminal

- 1553: Prince Mustafa, heir to Suleiman the Magnificent

- 1536: William Tyndale, English Bible translator

- 1849: Lajos Batthyány and the 13 Martyrs of Arad

Mikulich was an army lieutenant in 1944, who became part of the circle of officers plotting a national uprising against the German occupation.

Mikulich was an army lieutenant in 1944, who became part of the circle of officers plotting a national uprising against the German occupation.

Benny Swim(m) grew up on a squalid backwoods farm in the New Brunswick “badlands” where violence and moonshine were as ubiquitous as poverty: “the poorest human beings I have ever met in a civilized country,” in the words of an English observer who chanced to meet the story’s principals on a hunting trip before they made the crime headlines.

Benny Swim(m) grew up on a squalid backwoods farm in the New Brunswick “badlands” where violence and moonshine were as ubiquitous as poverty: “the poorest human beings I have ever met in a civilized country,” in the words of an English observer who chanced to meet the story’s principals on a hunting trip before they made the crime headlines. The Prince of Tang had spent essentially the whole of his adult life seeing the state eaten away by sclerotic bureaucracy, internal revolts, economic breakdown … and, as a consequence of all that erosion, by

The Prince of Tang had spent essentially the whole of his adult life seeing the state eaten away by sclerotic bureaucracy, internal revolts, economic breakdown … and, as a consequence of all that erosion, by