(Thanks to Emma Goldman for the guest post on her anarchist contemporary; it originally appeared in her Anarchism and Other Essays -ed.)

Experience has come to be considered the best school of life. The man or woman who does not learn some vital lesson in that school is looked upon as a dunce indeed. Yet strange to say, that though organized institutions continue perpetuating errors, though they learn nothing from experience, we acquiesce, as a matter of course.

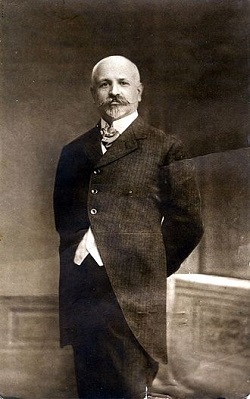

There lived and worked in Barcelona a man by the name of Francisco Ferrer. A teacher of children he was, known and loved by his people. Outside of Spain only the cultured few knew of Francisco Ferrer’s work. To the world at large this teacher was non-existent.

There lived and worked in Barcelona a man by the name of Francisco Ferrer. A teacher of children he was, known and loved by his people. Outside of Spain only the cultured few knew of Francisco Ferrer’s work. To the world at large this teacher was non-existent.

On the first of September, 1909, the Spanish government — at the behest of the Catholic Church — arrested Francisco Ferrer. On the thirteenth of October, after a mock trial, he was placed in the ditch at Montjuich prison, against the hideous wall of many sighs, and shot dead. Instantly Ferrer, the obscure teacher, became a universal figure, blazing forth the indignation and wrath of the whole civilized world against the wanton murder.

The killing of Francisco Ferrer was not the first crime committed by the Spanish government and the Catholic Church. The history of these institutions is one long stream of fire and blood. Still they have not learned through experience, nor yet come to realize that every frail being slain by Church and State grows and grows into a mighty giant, who will some day free humanity from their perilous hold.

Francisco Ferrer was born in 1859, of humble parents. They were Catholics, and therefore hoped to raise their son in the same faith. They did not know that the boy was to become the harbinger of a great truth, that his mind would refuse to travel in the old path. At an early age Ferrer began to question the faith of his fathers. He demanded to know how it is that the God who spoke to him of goodness and love would mar the sleep of the innocent child with dread and awe of tortures, of suffering, of hell. Alert and of a vivid and investigating mind, it did not take him long to discover the hideousness of that black monster, the Catholic Church. He would have none of it.

Francisco Ferrer was not only a doubter, a searcher for truth; he was also a rebel. His spirit would rise in just indignation against the iron régime of his country, and when a band of rebels, led by the brave patriot General Villacampa, under the banner of the Republican ideal, made an onslaught on that regime, none was more ardent a fighter than young Francisco Ferrer. The Republican ideal, — I hope no one will confound it with the Republicanism of this country. Whatever objection I, as an Anarchist, have to the Republicans of Latin countries, I know they tower high above that corrupt and reactionary party which, in America, is destroying every vestige of liberty and justice. One has but to think of the Mazzinis, the Garibaldis, the scores of others, to realize that their efforts were directed, not merely against the overthrow of despotism, but particularly against the Catholic Church, which from its very inception has been the enemy of all progress and liberalism.

In America it is just the reverse. Republicanism stands for vested rights, for imperialism, for graft, for the annihilation of every semblance of liberty. Its ideal is the oily, creepy respectability of a McKinley, and the brutal arrogance of a Roosevelt.

The Spanish republican rebels were subdued. It takes more than one brave effort to split the rock of ages, to cut off the head of that hydra monster, the Catholic Church and the Spanish throne. Arrest, persecution, and punishment followed the heroic attempt of the little band. Those who could escape the bloodhounds had to flee for safety to foreign shores. Francisco Ferrer was among the latter. He went to France.

How his soul must have expanded in the new land! France, the cradle of liberty, of ideas, of action. Paris, the ever young, intense Paris, with her pulsating life, after the gloom of his own belated country, — how she must have inspired him. What opportunities, what a glorious chance for a young idealist.

Francisco Ferrer lost no time. Like one famished he threw himself into the various liberal movements, met all kinds of people, learned, absorbed, and grew. While there, he also saw in operation the Modern School, which was to play such an important and fatal part in his life.

The Modern School in France was founded long before Ferrer’s time. Its originator, though on a small scale, was that sweet spirit Louise Michel. Whether consciously or unconsciously, our own great Louise felt long ago that the future belongs to the young generation; that unless the young be rescued from that mind and soul-destroying institution, the bourgeois school, social evils will continue to exist. Perhaps she thought, with Ibsen, that the atmosphere is saturated with ghosts, that the adult man and woman have so many superstitions to overcome. No sooner do they outgrow the deathlike grip of one spook, lo! they find themselves in the thraldom of ninety-nine other spooks. Thus but a few reach the mountain peak of complete regeneration.

The child, however, has no traditions to overcome. Its mind is not burdened with set ideas, its heart has not grown cold with class and caste distinctions. The child is to the teacher what clay is to the sculptor. Whether the world will receive a work of art or a wretched imitation, depends to a large extent on the creative power of the teacher.

…

Francisco Ferrer could not escape this great wave of Modern School attempts. He saw its possibilities, not merely in theoretic form, but in their practical application to every-day needs. He must have realized that Spain, more than any other country, stands in need of just such schools, if it is ever to throw off the double yoke of priest and soldier.

When we consider that the entire system of education in Spain is in the hands of the Catholic Church, and when we further remember the Catholic formula, “To inculcate Catholicism in the mind of the child until it is nine years of age is to ruin it forever for any other idea,” we will understand the tremendous task of Ferrer in bringing the new light to his people. Fate soon assisted him in realizing his great dream.

Mlle. Meunier, a pupil of Francisco Ferrer, and a lady of wealth, became interested in the Modern School project. When she died, she left Ferrer some valuable property and twelve thousand francs yearly income for the School.

It is said that mean souls can conceive of naught but mean ideas. If so, the contemptible methods of the Catholic Church to blackguard Ferrer’s character, in order to justify her own black crime, can readily be explained. Thus the lie was spread in American Catholic papers that Ferrer used his intimacy with Mlle. Meunier to get passession of her money.

Personally, I hold that the intimacy, of whatever nature, between a man and a woman, is their own affair, their sacred own. I would therefore not lose a word in referring to the matter, if it were not one of the many dastardly lies circulated about Ferrer. Of course, those who know the purity of the Catholic clergy will understand the insinuation. Have the Catholic priests ever looked upon woman as anything but a sex commodity? The historical data regarding the discoveries in the cloisters and monasteries will bear me out in that. How, then, are they to understand the co-operation of a man and a woman, except on a sex basis?

As a matter of fact, Mlle. Meunier was considerably Ferrer’s senior. Having spent her childhood and girlhood with a miserly father and a submissive mother, she could easily appreciate the necessity of love and joy in child life. She must have seen that Francisco Ferrer was a teacher, not college, machine, or diploma-made, but one endowed with genius for that calling.

Equipped with knowledge, with experience, and with the necessary means; above all, imbued with the divine fire of his mission, our Comrade came back to Spain, and there began his life’s work. On the ninth of September, 1901, the first Modern School was opened. It was enthusiastically received by the people of Barcelona, who pledged their support. In a short address at the opening of the School, Ferrer submitted his program to his friends. He said: “I am not a speaker, not a propagandist, not a fighter. I am a teacher; I love children above everything. I think I understand them. I want my contribution to the cause of liberty to be a young generation ready to meet a new era.” He was cautioned by his friends to be careful in his opposition to the Catholic Church. They knew to what lengths she would go to dispose of an enemy. Ferrer, too, knew. But, like Brand, he believed in all or nothing. He would not erect the Modern School on the same old lie. He would be frank and honest and open with the children.

Francisco Ferrer became a marked man. From the very first day of the opening of the School, he was shadowed. The school building was watched his little home in Mangat was watched. He was followed every step, even when he went to France or England to confer with his colleagues. He was a marked man, and it was only a question of time when the lurking enemy would tighten the noose.

It succeeded, almost, in 1906, when Ferrer was implicated in the attempt on the life of Alfonso. The evidence exonerating him was too strong even for the black crows; they had to let him go — not for good, however. They waited. Oh, they can wait, when they have set themselves to trap a victim.

The moment came at last, during the anti-military uprising in Spain, in July, 1909. One will have to search in vain the annals of revolutionary history to find a more remarkable protest against militarism. Having been soldier-ridden for centuries, the people of Spain could stand the yoke no longer. They would refuse to participate in useless slaughter. They saw no reason for aiding a despotic government in subduing and oppressing a small people fighting for their independence, as did the brave Riffs. No, they would not bear arms against them.

For eighteen hundred years the Catholic Church has preached the gospel of peace. Yet, when the people actually wanted to make this gospel a living reality, she urged the authorities to force them to bear arms. Thus the dynasty of Spain followed the murderous methods of the Russian dynasty, — the people were forced to the battlefield.

Then, and not until then, was their power of endurance at an end. Then, and not until then, did the workers of Spain turn against their masters, against those who, like leeches, had drained their strength, their very life — blood. Yes, they attacked the churches and the priests, but if the latter had a thousand lives, they could not possibly pay for the terrible outrages and crimes perpetrated upon the Spanish people.

Francisco Ferrer was arrested on the first of September, 1909. Until October first his friends and comrades did not even know what had become of him. On that day a letter was received by L’Humanité from which can be learned the whole mockery of the trial. And the next day his companion, Soledad Villafranca, received the following letter:

No reason to worry; you know I am absolutely innocent. Today I am particularly hopeful and joyous. It is the first time I can write to you, and the first time since my arrest that I can bathe in the rays of the sun, streaming generously through my cell window. You, too, must be joyous.

How pathetic that Ferrer should have believed, as late as October fourth, that he would not be condemned to death. Even more pathetic that his friends and comrades should once more have made the blunder in crediting the enemy with a sense of justice. Time and again they had placed faith in the judicial powers, only to see their brothers killed before their very eyes. They made no preparation to rescue Ferrer, not even a protest of any extent; nothing. “Why, it is impossible to condemn Ferrer; he is innocent.” But everything is possible with the Catholic Church. Is she not a practiced henchman, whose trials of her enemies are the worst mockery of justice?

On October fourth Ferrer sent the following letter to L’Humanite:

The Prison Cell, Oct. 4, 1909.

My dear Friends — Notwithstanding most absolute innocence, the prosecutor demands the death penalty, based on denunciations of the police, representing me as the chief of the world’s Anarchists, directing the labor syndicates of France, and guilty of conspiracies and insurrections everywhere, and declaring that my voyages to London and Paris were undertaken with no other object.

With such infamous lies they are trying to kill me.

The messenger is about to depart and I have not time for more. All the evidence presented to the investigating judge by the police is nothing but a tissue of lies and calumnious insinuations. But no proofs against me, having done nothing at all.

FERRER.

October thirteenth, 1909, Ferrer’s heart, so brave, so staunch, so loyal, was stilled. Poor fools! The last agonized throb of that heart had barely died away when it began to beat a hundredfold in the hearts of the civilized world, until it grew into terrific thunder, hurling forth its malediction upon the instigators of the black crime. Murderers of black garb and pious mien, to the bar of justice!

Did Francisco Ferrer participate in the anti-military uprising? According to the first indictment, which appeared in a Catholic paper in Madrid, signed by the Bishop and all the prelates of Barcelona, he was not even accused of participation. The indictment was to the effect that Francisco Ferrer was guilty of having organized godless schools, and having circulated godless literature. But in the twentieth century men can not be burned merely for their godless beliefs. Something else had to be devised; hence the charge of instigating the uprising.

In no authentic source so far investigated could a single proof be found to connect Ferrer with the uprising. But then, no proofs were wanted, or accepted, by the authorities. There were seventy-two witnesses, to be sure, but their testimony was taken on paper. They never were confronted with Ferrer, or he with them.

Is it psychologically possible that Ferrer should have participated? I do not believe it is, and here are my reasons. Francisco Ferrer was not only a great teacher, but he was also undoubtedly a marvelous organizer. In eight years, between 1901–1909, he had organized in Spain one hundred and nine schools, besides inducing the liberal element of his country to organize three hundred and eight other schools. In connection with his own school work, Ferrer had equipped a modern printing plant, organized a staff of translators, and spread broadcast one hundred and fifty thousand copies of modern scientific and sociologic works, not to forget the large quantity of rationalist text books. Surely none but the most methodical and efficient organizer could have accomplished such a feat.

On the other hand, it was absolutely proven that the anti-military uprising was not at all organized; that it came as a surprise to the people themselves, like a great many revolutionary waves on previous occasions. The people of Barcelona, for instance, had the city in their control for four days, and, according to the statement of tourists, greater order and peace never prevailed. Of course, the people were so little prepared that when the time came, they did not know what to do. In this regard they were like the people of Paris during the Commune of 1871. They, too, were unprepared. While they were starving, they protected the warehouses filled to the brim with provisions. They placed sentinels to guard the Bank of France, where the bourgeoisie kept the stolen money. The workers of Barcelona, too, watched over the spoils of their masters.

How pathetic is the stupidity of the underdog; how terribly tragic! But, then, have not his fetters been forged so deeply into his flesh, that he would not, even if he could, break them? The awe of authority, of law, of private property, hundredfold burned into his soul, — how is he to throw it off unprepared, unexpectedly?

Can anyone assume for a moment that a man like Ferrer would affiliate himself with such a spontaneous, unorganized effort? Would he not have known that it would result in a defeat, a disastrous defeat for the people? And is it not more likely that if he would have taken part, he, the experienced entrepreneur, would have thoroughly organized the attempt? If all other proofs were lacking, that one factor would be sufficient to exonerate Francisco Ferrer. But there are others equally convincing.

For the very date of the outbreak, July twenty-fifth, Ferrer had called a conference of his teachers and members of the League of Rational Education. It was to consider the autumn work, and particularly the publication of Elisée Reclus‘ great book, L’Homme et la Terre, and Peter Kropotkin‘s Great French Revolution. Is it at all likely, is it at all plausible that Ferrer, knowing of the uprising, being a party to it, would in cold blood invite his friends and colleagues to Barcelona for the day on which he realized their lives would be endangered? Surely, only the criminal, vicious mind of a Jesuit could credit such deliberate murder.

Francisco Ferrer had his life-work mapped out; he had everything to lose and nothing to gain, except ruin and disaster, were he to lend assistance to the outbreak. Not that he doubted the justice of the people’s wrath; but his work, his hope, his very nature was directed toward another goal.

In vain are the frantic efforts of the Catholic Church, her lies, falsehoods, calumnies. She stands condemned by the awakened human conscience of having once more repeated the foul crimes of the past.

Francisco Ferrer is accused of teaching the children the most blood-curdling ideas, — to hate God, for instance. Horrors! Francisco Ferrer did not believe in the existence of a God. Why teach the child to hate something which does not exist? Is it not more likely that he took the children out into the open, that he showed them the splendor of the sunset, the brilliancy of the starry heavens, the awe-inspiring wonder of the mountains and seas; that he explained to them in his simple, direct way the law of growth, of development, of the interrelation of all life? In so doing he made it forever impossible for the poisonous weeds of the Catholic Church to take root in the child’s mind.

It has been stated that Ferrer prepared the children to destroy the rich. Ghost stories of old maids. Is it not more likely that he prepared them to succor the poor? That he taught them the humiliation, the degradation, the awfulness of poverty, which is a vice and not a virtue; that he taught the dignity and importance of all creative efforts, which alone sustain life and build character. Is it not the best and most effective way of bringing into the proper light the absolute uselessness and injury of parasitism?

Last, but not least, Ferrer is charged with undermining the army by inculcating anti-military ideas. Indeed? He must have believed with Tolstoy that war is legalized slaughter, that it perpetuates hatred and arrogance, that it eats away the heart of nations, and turns them into raving maniacs.

However, we have Ferrer’s own word regarding his ideas of modern education:

I would like to call the attention of my readers to this idea: All the value of education rests in the respect for the physical, intellectual, and moral will of the child. Just as in science no demonstration is possible save by facts, just so there is no real education save that which is exempt from all dogmatism, which leaves to the child itself the direction of its effort, and confines itself to the seconding of its effort. Now, there is nothing easier than to alter this purpose, and nothing harder than to respect it. Education is always imposing, violating, constraining; the real educator is he who can best protect the child against his (the teacher’s) own ideas, his peculiar whims; he who can best appeal to the child’s own energies.

We are convinced that the education of the future will be of an entirely spontaneous nature; certainly we can not as yet realize it, but the evolution of methods in the direction of a wider comprehension of the phenomena of life, and the fact that all advances toward perfection mean the overcoming of restraint, — all this indicates that we are in the right when we hope for the deliverance of the child through science.

Let us not fear to say that we want men capable of evolving without stopping, capable of destroying and renewing their environments without cessation, of renewing themselves also; men, whose intellectual independence will be their greatest force, who will attach themselves to nothing, always ready to accept what is best, happy in the triumph of new ideas, aspiring to live multiple lives in one life. Society fears such men; we therefore must not hope that it will ever want an education able to give them to us.

We shall follow the labors of the scientists who study the child with the greatest attention, and we shall eagerly seek for means of applying their experience to the education which we want to build up, in the direction of an ever fuller liberation of the individual. But how can we attain our end? Shall it not be by putting ourselves directly to the work favoring the foundation of new schools, which shall be ruled as much as possible by this spirit of liberty, which we forefeel will dominate the entire work of education in the future?

A trial has been made, which, for the present, has already given excellent results. We can destroy all which in the present school answers to the organization of constraint, the artificial surroundings by which children are separated from nature and life, the intellectual and moral discipline made use of to impose ready-made ideas upon them, beliefs which deprave and annihilate natural bent. Without fear of deceiving ourselves, we can restore the child to the environment which entices it, the environment of nature in which he will be in contact with all that he loves, and in which impressions of life will replace fastidious book-learning. If we did no more than that, we should already have prepared in great part the deliverance of the child.

In such conditions we might already freely apply the data of science and labor most fruitfully.

I know very well we could not thus realize all our hopes, that we should often be forced, for lack of knowledge, to employ undesirable methods; but a certitude would sustain us in our efforts — namely, that even without reaching our aim completely we should do more and better in our still imperfect work than the present school accomplishes. I like the free spontaneity of a child who knows nothing, better than the world-knowledge and intellectual deformity of a child who has been subjected to our present education.

Had Ferrer actually organized the riots, had he fought on the barricades, had he hurled a hundred bombs, he could not have been so dangerous to the Catholic Church and to despotism, as with his opposition to discipline and restraint. Discipline and restraint — are they not back of all the evils in the world? Slavery, submission, poverty, all misery, all social iniquities result from discipline and restraint. Indeed, Ferrer was dangerous. Therefore he had to die, October thirteenth, 1909, in the ditch of Montjuich. Yet who dare say his death was in vain? In view of the tempestuous rise of universal indignation: Italy naming streets in memory of Francisco Ferrer, Belgium inaugurating a movement to erect a memorial; France calling to the front her most illustrious men to resume the heritage of the martyr; England being the first to issue a biography; all countries uniting in perpetuating the great work of Francisco Ferrer; America, even, tardy always in progressive ideas, giving birth to a Francisco Ferrer Association, its aim being to publish a complete life of Ferrer and to organize Modern Schools all over the country, — in the face of this international revolutionary wave, who is there to say Ferrer died in vain?

That death at Montjuich, — how wonderful, how dramatic it was, how it stirs the human soul. Proud and erect, the inner eye turned toward the light, Francisco Ferrer needed no lying priests to give him courage, nor did he upbraid a phantom for forsaking him. The consciousness that his executioners represented a dying age, and that his was the living truth, sustained him in the last heroic moments.

A dying age and a living truth,

The living burying the dead.

On this day..

- 1998: Jeremy Vargas Sagastegui - 2020

- 1941: Bronislava Poskrebysheva - 2019

- 1762: James Collins, James Whem, and John Kello - 2018

- 1960: Tony Zarba, anti-Castro raider - 2017

- 1871: James Wilson, steely burglar - 2016

- 1990: The October 13 Massacre - 2014

- 1944: Six German POWs, for Stalingrad's Dulag-205 - 2013

- 1933: Morris Cohen, medicine-taker - 2012

- 1864: Ranger A.C. Willis, parabolically - 2011

- 1846: William Westwood, aka Jackey Jackey - 2010

- 1815: Joachim Murat, Napoleonic Marshal - 2009

- 1660: Major-General Thomas Harrison, the first of the regicides - 2008

There lived and worked in

There lived and worked in

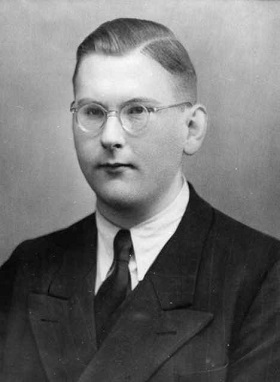

Born to a globetrotting journalist, the young polyglot

Born to a globetrotting journalist, the young polyglot

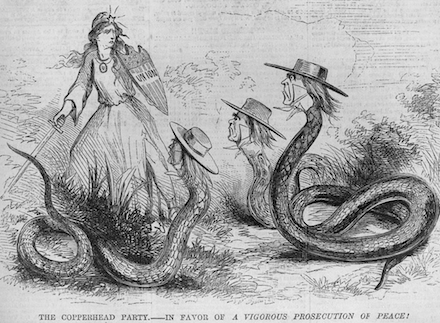

Our man Milligan was one of these Copperhead Indiana Democrats born to test Washington’s elasticity. He was an exponent of the

Our man Milligan was one of these Copperhead Indiana Democrats born to test Washington’s elasticity. He was an exponent of the  Only 19 years old,

Only 19 years old,