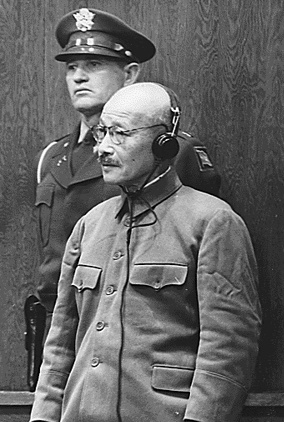

On this date in 1948, seven “Class A” war criminals, including Japan’s wartime Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, were hanged at Sugamo Prison by the American occupation authorities.

Like other Axis heads of state, Tojo was in for a bad end: he shot himself in the chest before American troops could arrest him, but missed his heart even though a doctor had helpfully marked the spot on his chest for him.

However inevitable Tojo’s postwar fate, however, he was not exactly of a kind with the likes of Hitler and Mussolini. Indeed, he’d been cashiered from his Prime Ministerial gig in 1944 by the real power behind the throne — the Japanese military.

However inevitable Tojo’s postwar fate, however, he was not exactly of a kind with the likes of Hitler and Mussolini. Indeed, he’d been cashiered from his Prime Ministerial gig in 1944 by the real power behind the throne — the Japanese military.

Unlike the “Fuhrer” and “Il Duce,” Tojo was a reflector, not a creator, of national thought. His word was not law. It was not his command or dictate. He was one among many and not even the first among equals. He was a militarist — misguided, naive, and narrow in outlook; he regarded war as a legitimate instrument of national policy; he apparently believed what he told the court, and failed to recognize the patent contradictions between his contentions and the facts. This had been his undoing.

That’s Robert Butow in Tojo and the Coming of War. Butow argues that the titular authority in Japan (he became Prime Minister shortly before the bombing of Pearl Harbor), a dedicated, patriotic officer of adequate talents but limited vision, came much too late and controlled much too little to be seen as the equal of the European theater’s villains.

The Japan of which General Hideki Tojo became premier was operated by remote control. It was a country in which puppet politics had reached a high state of development, to the detriment of the national welfare. The ranking members of the military services were the robots of their subordinates — the so-called chuken shoko, the nucleus group, which was active “at the center” and which was composed largely of field-grade officers. They, in turn, were influenced by younger elements within the services at large and by ultranationalists outside military ranks. The civilian members of the cabinet were the robots of the military — especially of the nucleus group, working through the service ministers and the chiefs of the army and navy general staffs. The Emperor himself, through no fault of his own, was the robot of the government — of the cabinet and the supreme command, a prisoner of the circumstances into which he was born … Finally, the nation — the one hundred million dedicated souls, the sum and substance of Japan, from whom the blood and toil and tears and sweat of Churchill’s phrase were wrung — the nation was the robot of the throne.

He was the man for his time and place. He fit right in.

Even when being fitted for a noose.

Once Tojo had recovered from his errant self-inflicted wound,* and even though he had been among those opposing surrender even after the atomic bombings, he played ball with the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (whose trial transcripts run to 50,000 pages).

The former premier embraced responsibility, diligently shielding the Emperor from any intimation of guilt (some argue this was the procedure’s entire raison d’etre, from the perspective of both the prosecution and the defense), and walked a dignified and honorable last mile in the courtrooms of the victor’s justice, presenting his perspective as he knew it in the context of a wish for peace between the late antagonists.

1. I deny that Japan “declared war on civilization.”

2. To advocate a New Order was to seek freedom and respect for peoples without prejudice, and to seek a stable basis for the existence all peoples, equally, and free of threats. Thus, it was to seek true civilization and true justice for all the peoples of the world, and to view this as the destruction of personal freedom and respect is to be assailed by the hatred and emotion of war, and to make hasty judgments.

3. I would like to point out their [my accusers’] inhumane and uncivilized actions in East Asia ever since the Middle Ages.

4. In the shadow of the prosperity of Europe and America, the colored peoples of East Asia and Africa have been sacrificed and forced into a state of semi-colonization. I would point out that the cultural advance of these people has been suppressed in the past and continues to be suppressed in the present by policies designed to keep them in ignorance.

5. I would point out that Japan’s proposal at the Versailles Peace Conference on the principle of racial equality was rejected by delegates such as those from Britain and the United States.

6. Of two through five above, which is civilization? Which is international justice? Justice has nothing to do with victor nations and vanquished nations, but must be a moral standard that all the world’s peoples can agree to. To seek this and to achieve it — that is true civilization.

7. In order to understand this, all nations must hate war, forsake emotion, reflect upon their pasts, and think calmly.

The “Class A” convicts not executed along with Tojo were freed afterwards.

Tojo has enjoyed a bit of a latter-day resurgence in the public regard, product of the nationalist right’s resurgence in Japan. The hanged man’s granddaughter Yuko Tojo has waged a tireless campaign to clear him.

Further to that end, his ashes — and those of the other Class A convicts — were covertly added to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, and remain there to this day. That public tribute to principals of Japan’s bloody foreign occupations has become a hot political football between Japan and other nations, especially China.

But after all, Tojo the man was never a leper, but part and parcel of his times. Small wonder that we moderns hear an echo of the general’s postwar justification for the War in the Pacific from the country that hanged him.

Japan … faced considerable military threats as well.

Japan attempted to circumvent these dangerous circumstances by diplomatic negotiation, and though Japan heaped concession upon concession, in the hope of finding a solution through mutual compromise, there was no progress because the United States would not retreat from its original position. …

Since events had progressed as they had, it became clear that to continue in this manner was to lead the nation to disaster. With options thus foreclosed, in order to protect and defend the nation and clear the obstacles that stood in its path, a decisive appeal to arms was made.

The problematic nature of the war crimes proceedings in postwar Japan (especially vis-a-vis those in Germany) is examined in Yuma Totani’s The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Pursuit of Justice in the Wake of World War II. The author discussed her research on the New Books In History podcast.

[audio:http://newbooksinhistory.com/podpress_trac/web/720/0/Totani%20Interview.mp3]* According to John Dower’s Embracing Defeat, the suicide scenario angered some nationalists because Tojo only “belatedly summoned the will to die,” and “chose the foreigner’s way of the bullet rather than the samurai’s way of the sword, and then botched even this.”

On this day..

- 1521: The rebel Ribbings

- 1572: Johann Sylvan, Antitrinitarian

- 1856: Three Italian seamen in Hampshire

- 1569: Orthodox Metropolitan Philip II of Moscow

- 1736: Ana de Castro and two Jesuit effigies in a Lima auto de fe

- 1679: "A number of poor people for the crime of witchcraft"

- 1605: Niklaus von Gulchen, Nuremberg privy councillor

- 1926: Petrus Stephanus Hauptfleisch, mother-murderer

- 1799: Isaac Yeshurun Sasportas, anti-slavery insurrectionist

- 1942: Sasha Filippov, during the Battle of Stalingrad

- 1953: Lavrenty Beria, Stalin henchman

- 1559: Anne du Bourg