On this date in 1625, Helene Gillet went to the scaffold in Dijon to suffer beheading for infanticide.

But it was the executioner and not Helene who came down from it in pieces.

Helene was the beautiful 21-year-old daughter of a royal chatelain, the sort of well-to-do folks who would own monogrammed blankets that proved quite incriminating when found wrapped around an abandoned dead infant in the woods. Helene would claim that its origin was a family tutor who forced himself upon her, and also insist without further explanation on her innocence of the child’s fate — though the latter little entered the picture since an edict from 1556 made it capital crime to conceal pregnancy and childbirth.

Thanks to her status, she was entitled to the dignity of a beheading, rather than an ignoble dispatch by rope. But all else for Helene Gillet was shame: her father disowned her and forbade any intervention on her behalf; only Helen’s mother accompanied her to Dijon to appeal against the sentence.

It is said that in the course of her appeals to the Parlement of Dijon, the mother attracted the sympathy of the Bernadine abbey there, one of whose inmates ventured to prophesy that “whatever happens, Helene Gillet will not die by the hand of the executioner, but will die a natural and edifying death.”

Parlement begged to differ.

On Monday, May 12th, the young woman was led to the hill of Morimont (present-day Place Emile-Zola) by the executioner of Dijon, Simon Grandjean. Monsieur Bourreau was in an agitated state that day, whether from pity for his victim, or from an ague that had afflicted him, or from whatever other woes haunted his life. When you’re the executioner of Dijon you can’t just call in sick or take a mental health day.

The scaffold on which the whole tragedy was to unfold was a permanent edifice, albeit far less monumental than the likes of Montfaucon. Its routine employment was attested by the permanent wooden palisade and the small stone chapel comprising the arena — features that would factor in the ensuing scene.

Having positioned Gillet on the block, our troubled executioner raised up his ceremonial sword and brought it crashing down … on her left shoulder. The blow toppled the prisoner from the block, but she was quite alive. To cleanly strike through a living neck with a hand-swung blade — to do so under thousands of hostile eyes — was never a certain art; there are many similar misses in the annals. Often, an headsman’s clumsiness in his office would incite the crowd: the legendary English executioner Jack Ketch was nearly lynched for his ten-thumbed performance beheading Lord Monmouth; the hangman of Florence had been stoned to death by an enraged mob after a badly botched execution in 1503.

The Dijonnaise were no more forgiving of Grandjean. Hoots and missiles began pelting the platform as the pitiable condemned, matted with blood, struggled back to the block — and Grandjean must have felt the rising gorge and sweated hands of the man who knows an occasion is about to unman him.

Grandjean’s wife, who acted his assistant in his duties, vainly strove to rescue her man’s mettle and the situation. One chop would do it: the struggling patient would still, the archer detail would restrain the angry crowd. Madame Grandjean forced Gillet back to the block, thrust the dropped sword back into the executioner’s hands with who knows what exhortation.

What else could he do? Again the high executioner raised the blade and again arced it down on the young woman’s head — and again goggled in dismay. Somehow, the blow had been half-deflected by a knot of Helene Gillet’s hair, and nicked only a small gash in the supplicant’s neck. Now hair is a decided inconvenience for this line of work and it was customary to cut it or tie it up — even the era of the guillotine gives us the infamous pre-execution toilette. Even so, the idea of a strong and vigorous man brandishing a heavy executioner’s sword being so entirely frustrated by a braid puts us in mind of an athlete short-arming a free throw or skying a penalty kick for want of conviction in the motion.

This is, admittedly, a retrospective interpretation, but if Grandjean had any inkling of what was to follow one could forgive him the choke.

Having now seen the vulnerable youth survive two clumsy swipes, the crowd’s fury poured brickbats onto the stage in a flurry sufficient to drive the friars who accompanied the condemned to flee in fear for their own lives. Grandjean followed them, all of them retreating to the momentary safety of the chapel as the attempted execution collapsed into chaos.

The steelier Madame Grandjean tried to salvage matters by completing what her husband could not — and seized the injured Gillet to haul her off the platform to the partial shelter of the stone risers by which they had ascended, like a tiger dragging prey to its lair. No longer bothering with the ceremonial niceties of the office, Madame Grandjean simply began kicking and beating Gillet as she drew out a pair of shears to finish her off in violent intimacy.

But the raging mob by this time had pushed through the guards and overrun the palisades, and fell on the melee in the midst of Madame Grandjean’s fevered slashing. The executioner’s wife was ruthlessly torn to pieces, and the cowering executioner himself soon forced from his refuge to the same fate.

Helene Gillet, who had survived a beheading, was hauled by her saviors bloody and near-senseless to a nearby surgeon, who tended her injuries and confirmed that none of them ought be fatal.

What would happen to her now?

The prerogatives of the state insist against the popular belief in pardoning an execution survivor.

We don’t have good answers for this situation even today; that a person might leave their own execution alive seems inadmissible, even though it does — still — occur.

But Helene Gillet was obviously a sympathetic case, and as a practical matter, the office of Dijon executioner had suddenly become vacant. The city’s worthies petitioned as one for her reprieve.

As it happened, King Louis XIII’s younger sister Henrietta Maria had on the very day preceding the execution been married by proxy to Louis’s ill-fated English counterpart Charles I. This gave the French sovereign good occasion for the very palatable exercise of mercy, “at the recommendation of some of our beloved and respected servants, and because we are well-disposed to be gracious through the happy marriage of the Queen of Great Britain.”

The Parlement of Dijon received the royal pardon on June 2, and formally declared Helene Gillet’s official acquittal.

The fortunate woman, having had a brush with the sublime, is said to have retired herself to a convent and lived out the best part of the 17th century there in prayer.

There’s a 19th century French pamphlet of documents related to this case available from Google books.

On this day..

- 1944: Oskar Kusch, Wehrkraftzersetzung U-boat commander

- 1899: Claude Branton, gallows photograph

- 1974: Leyla Qasim, Bride of Kurdistan

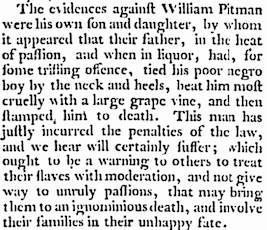

- 1775: William Pitman, for murdering his slave

- 1868: Robert Smith, the last publicly hanged in Scotland

- 1543: Jakob Karrer, Vesalius subject

- 1936: Buck Ruxton, red stains

- 1388: Three evil counselors of Richard II

- 1730: James Dalton, Hogarth allusion

- 1641: Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

- 1993: Leonel Herrera, perilously close to simple murder?

- 1916: James Connolly, socialist revolutionary

And on top of all the intrinsic perils of fighting a losing war from the inside of a submerged tin of beans, you’d better do it with enthusiasm or you’ve got the prospect of going up against the wall like Oskar Kusch did on May 12, 1944.

And on top of all the intrinsic perils of fighting a losing war from the inside of a submerged tin of beans, you’d better do it with enthusiasm or you’ve got the prospect of going up against the wall like Oskar Kusch did on May 12, 1944.

Though inclement Scottish weather kept the crowds at bay on the occasion, Robert Smith was a notorious villain for his season in the public eye, as the ensuing newspaper reports will attest.

Though inclement Scottish weather kept the crowds at bay on the occasion, Robert Smith was a notorious villain for his season in the public eye, as the ensuing newspaper reports will attest.

A general practitioner of Persian descent, Ruxton was born in India and moved to the United Kingdom in 1930 to set up practice in Lancaster.

A general practitioner of Persian descent, Ruxton was born in India and moved to the United Kingdom in 1930 to set up practice in Lancaster.