If the “revolutionary extremist” exists at all as an identifiable type, he exists in purest incarnation in Gracchus Babeuf. No revolutionary better fits the description “narrowminded to the point of genius”; few have defined their heaven more clearly or crusaded so fanatically, ascetically, so religiously to bring it to earth.

–Gracchus Babeuf: The First Revolutionary Communist

On this date in 1797, Francois-Noel Babeuf lost his head for the Conspiracy of Equals — the last Jacobin upheaval of the French Revolution, or the first Communist upheaval of post-Revolution modernity.

On this date in 1797, Francois-Noel Babeuf lost his head for the Conspiracy of Equals — the last Jacobin upheaval of the French Revolution, or the first Communist upheaval of post-Revolution modernity.

Francois-Noel — he styled himself “Gracchus” after the populist Roman tribunes — was a young man of Desmoulins‘ generation but from a considerably more hardscrabble background. Like the starry-eyed Dantonist scribbler, Babeuf discovered himself a brilliant journalist and pamphleteer with the onset of the Revolution; he did several prison stints during various revolutionary phases of the early 1790s for his too-radical-for-school opinions.

He did another in 1795 under the French Directory for his firebreathing rag Le Tribun du Peuple, which was particularly unfashionable stuff during the post-Robespierre Thermidorian regime.

Nothing daunted, Babeuf emerged from prison the leading apostle of the Parisian proletariat which had by then been decisively separated from power.

The order of the day was class consolidation with the spoils of the aristocracy apportioned among a new oligarchy of wealth. As France rushed headlong towards Bonaparte and Bourbon restoration, Babeuf was the man left to rally “the party which desires the reign of pure equality.”

The French Revolution was nothing but a precursor of another revolution, one that will be bigger, more solemn, and which will be the last.

The people marched over the bodies of kings and priests who were in league against it: it will do the same to the new tyrants, the new political Tartuffes seated in the place of the old.

–Manifesto of the Equals, 1796

One can see why later revolutionaries — Marx included; Babeuf makes a cameo in the Communist Manifesto — would adopt this sort of thing as a harbinger of the next century’s revolutions.

And if the Directory had known who Nicholas II would be, it would have had no intention of going the way of his family.

Instead, it shut him down in February, 1796: Napoleon Bonaparte personally carried out the operation, just days before he wed Josephine.

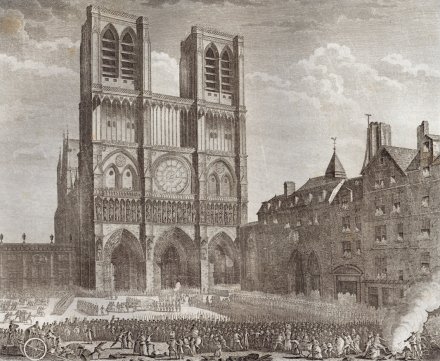

The Babeuf Conspiracy. Anonymous French print.

The Babeuf Conspiracy. Anonymous French print.Babeuf’s party comes down to us as a “conspiracy,” under which word the state would charge him and which his follower Philippe Buonarroti would later rebrand the “Conspiracy of Equals”. It was not so much a grassy-knoll type of conspiracy as it was an underground organization.

When its adherents placarded Paris with the seditious “Analysis of the Doctrine of Babeuf” as the city endured a potentially dangerous economic crisis in April 1796, the government was put to a test of its strength.

It passed.

Having infiltrated Babeuf’s network, it arrested the principals on the eve of the Conspiracy’s intended insurrection. They were hailed out of Paris (a safeguard against sympathetic risings) to the commune of Vendome and there put on trial.* Babeuf and his associate Augustin Alexandre Darthe were condemned to death on May 26th and guillotined the very next day.

The last gasp of the French Revolution dropped with their heads into the basket.

Revolutionary Babeuvism, however, had scarcely just begun.

I don’t know what will become of the republicans, their families, and even the babies still at their mothers’ breasts, in the midst of the royalist fury that the counter-revolution will bring. O my friends! How heart-rending these thoughts are in my final moments! … To die for the fatherland, to leave a family, children, a beloved wife, all would be bearable if at the end of this I didn’t see liberty lost and all that belongs to sincere republicans wrapped in a horrible proscription.

-Babeuf’s last letter to his family

* The trial of Babeuf was itself a jurisprudential milestone: it was the first French trial to be transcribed verbatim.

What might look today like a nifty little advance for efficient judicature was bitterly controversial in 1797. The French Revolution had overturned an ancien regime practice of professional magistrates accepting legal testimony by written deposition and deciding matters behind closed doors. The liberte, egalite, fraternite way would instead demand that testimony be given live in the courtroom where citizen jurors could weigh its credibility.

Babeuf’s lawyer, Pierre-Francois Real, protested against the court stenographers, arguing that “The law insists that the system of written depositions not be restored in any way. That system will undoubtedly return if any means are used to save testimony given orally.”

There’s a fascinating disquisition on the curious and contradictory development of this issue and the way it “violates … common assumptions about the advance of textuality in the West” during the French Revolution in Laura Mason, “The ‘Bosom of Proof’: Criminal Justice and the Renewal of Oral Culture during the French Revolution” The Journal of Modern History, March 2004.

On this day..

On this date in 1797,

On this date in 1797,

Antoine Quentin Fouquier de Tinville (

Antoine Quentin Fouquier de Tinville ( The

The