Public vengeance here is but half satiated and stern justice has only been one-half administered by the execution of Orme, for Brooks, who bore an equal part in the bloody deed, has escaped the clutches of the law, and has thus far defied pursuit.

A narrative of the murder, a sketch of the murderers, an account of the rial, the subsequent escape, and the final closing scene of the terrible tragedy is appended: —

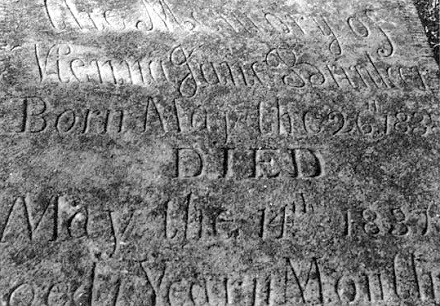

Theodore Brodhead, the murdered man, was a gentleman universally respected and esteemed, and was a brother of Thomas Brodhead, the proprietor of the Brainerd House, where the robbery occurred. He was formerly engaged in the lumber business, and was about 45 years of age.

William Brooks is a Scotchman by birth, 24 years old. He had been in the country one year and a half at the time of the murder. He landed at New York, and worked there a while, and then went wandering to get employment. He worked on railroads and at anything else, and was considered a hard case. Subsequently he turned up at Scranton and worked there. He said he was never arrested before on any charge, and that he could not remember firing the shot that killed Theodore Brodhead, as he was drunk at the time, and has no knowledge of having a pistol. He appeared much dejected and anxious to know if he would be convicted of the murder. He said he had been in Philadelphia and traveled a good deal.

Charles Orme was born in Ireland. He told contradictory stories about himself; said he was in the army, and worked two or three years in New York, and then as a brakeman on the Camden and Amboy Railroad. He was in trouble once “for covering swag.” He lived at Camden, and was familiar with Philadelphia. He was greatly depressed in spirits when arrested, and feared Lynch law, being very anxious to know, when placed in the Stroudsburg jail, if one or both of the Brodheads were killed.

Orme was not as intelligent as Brooks, and did not create such a bad impression. It appears that both men left Scranton together on a freight train, but were put off at Stroudsburg during Thursday, September 24, 1868. They wandered about Stroudsburg, and took drinks at the principal hotels. During that night they robbed a hardware store at Stroudsburg, and stole a lot of tools and a coat, and placed the proceeds of the robbery in a carpet bag and proceeded towards the Water Gap.

They stopped at the Brainerd House and got in with two or three laborers on Saturday morning, about ten o’clock, and took drinks with them, when they were left in the bar-room alone. They waited until Thomas Brodhead went out, and then quietly robbed the drawer of eight dollars. They then went to Luke Brodhead’s tavern, near the Brainerd House, and took a drink, after which they walked a short distance along the road, when they were overtaken by Thomas Brodhead, followed by Theodore.

They were counting and sharing the money when the Brodheads came up. Thomas accused them of the robbery, when they threw the money down, and said “Take the money.” Thomas then told them they must go back with him, when one of them appeared willing at first, and then refused. Thomas then advanced on Orme and grabbed him.

Orme attempted to throw some money over an orchard wall, but a two-dollar note fell to the ground, and as Thomas Brodhead stooped to pick it up, Brooks leveled a pistol at his head. Theodore warned him not to fire, and he turned and shot him (Theodore) through the heart. A scuffle ensued between Thomas and the men, in which several pistol shots were fired, and the former was so badly beaten that he sank to the ground exhausted, whereupon they fled.

They went down in the Gap and up in the mountains, and after wandering around found they were headed off, the whole neighborhood by this time being in arms and scouring the country for them. Without knowing it they took a cut and came out near the scene of the murder, there being nobody about, the citizens being in the mountains hunting them. They were soon seen, however, crossing the road and wading through Cherry creek, when the alarm was given and the spot was soon surrounded. They hid in some underbrush, but, when summoned, came forth and surrendered. One of them pointed a pistol at the crowd just before the surrender, but did not fire, and both captives threw away their weapons before being caught. There was great trouble to prevent them being lynched by the incensed citizens; the Sheriff and his men saved their lives with great difficulty. After a period of great excitement both men were lodged in the Stroudsburg jail, and the prison was guarded day and night. This was the only murder which had occurred in that section of the country for many years.

The prisoners were arraigned for trial on the 29th of December, and several days were taken up by the cause. They were represented by able counsel, but a verdict of “guilty of murder in the first degree” was returned. An appeal was then taken to the Supreme Court, upon the ground that the Brodheads, being private citizens, and having no warrant, their death, resulting from resistance to the attempted arrest, was not murder, but manslaughter. This the Court below refused to affirm, and this formed the principal assignment of error. The point was argued at length, but was overruled by the Supreme Court, the opinion stating: —

The Prisoners Break Jail.

On Saturday morning, April 3, the citizens of Stroudsburg were startled by the ringing of the alarm bell at three A.M. It soon became known that the prisoners had escaped, and speedily there was gathered at the jail an excited multitude, armed and unarmed, on horseback and on foot, ready to scour the country.

The facts of the escape may be summed up as follows: —

It seems one of the prisoners feigned sickness, and at length tumbled down on the floor of his cell as if in a fit or spasm. The other one called to the old jailer, who was watching in the hall, and asked him if he would come in and help him to lift his companion on the bed. The old man unsuspectingly unlocked the door of the cell, leaving the keys sticking in the lock. The prisoners at once sprang to their feet, commanding the jailer to keep still at the peril of his life. Their hopples [hobbles] and handcuffs they had previously removed without keys by hammering them open, and they now sprang out, closing the cell door on the old jailer, and were soon at liberty outside the jail. They had failed to lock the jailer in, so in a few minutes after their escape the bells rang out the alarm, and at an early hour the chase began. Couriers on horseback were sent out in every direction, while those on foot took to the fields and woods. A blodhound brought from Jersey for the purpose seemed to indicate that the fellows had made for the Pocose Mountains.

An examination of the empty cell led to the discovery of an opening in the wall almost sufficiently large to have admitted their exit from thence. It was made by sawing out a piece from an oak plank, about twelve or fourteen inches wide by two inches thick, and then digging almost through the main wall of the building. The sawing seems to have been done in the usual prisoner style, with a case-knife filed for the purpose. It must have taken many hours of labor. The stones taken from the wall were hide in their bed. Why they chose to operate on the old jailer instead of this opening was a mystery.

Throughout Saturday the excitement was very great in Stroudsburg and vicinity, and business came to a halt equal to the day of the murder. The Sheriff had offered a thousand dollars reward, private individuals had added other hundreds to the offer, and the pursuit was vigorous and earnest. Up to Sunday morning nothing had been heard from the criminals. Many of the pursuers had returned, declaring the chase in vain. At length, at about three o’clock in the afternoon, it was rumored that they had been captured. Soon after, a crowd approached Stroudsburg, when it was found that the prisoner Orme, was in custody, while Brooks was still at large.

Not being accustomed to exercise, they had found it difficult to flee from their pursuers, and were found in a barn of Mr. Long, on Sunday morning, only a few miles from Stroudsburg. A boy had gone into the barn, and on getting hay for his horse, had come upon them. They asked him if he would betray them. He said no. Going to the house, he told his father, who came to the barn, and promised the same thing. He took them to the house, gave them something to eat, and while they were eating, Long set out for Stroudsburg, where he inquired if he would get the reward if he informed the authorities where the prisoners were. Being answered in the affirmative, he told the story, when a party hurried back to the scene. Arriving at Long’s it was found that not only were the fugitives gone, but Long’s horses also. The party followed hastily on, and soon came in sight of the fleeing convicts. These, seeing their pursuers, and not being accustomed to horseback riding, left the horses and the road, and took to the woods in opposite directions. Orme was soon overtaken, when he turned around, threw open his arms, and begged to be shot on the spot. But he was returned to the jail, and to-day forfeited his life for the heinous crime, which certainly created both a greater amount of indignation and excitement than any other which ever occurred in Monroe county.

A Plea for Respite Fails.

Last evening Mr. Ridgway, the Minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church here, and spiritual adviser of the condemned man, received a telegraphic despatch from Harrisburg, sent by some of the friends and sympathizers of Orme, who visited Govenror Geary to endeavor to get a respite, that there was no hope of a reprieve, and that the sentence of the law would certainly be carried into effect. Mr. Ridgway informed Orme of this, and he received the news without any particular emotino, having made up his mind for the worst.

An Attempt to Escape.

It was discovered last evening, about five o’clock, that Orme had been making secret preparations to escape for the last three weeks. Some time ago a woman who visited his cell, informed him that a well-known horse thief, who occupied the same cell, had managed to effect an escape by filing off his chains, and getting through the window on to the roof. She also said that the horse thief left some things in the cell, but the keepers had never been able to find the file.

This was a hint for Orme, and he quietly commenced hunting for the file in corners and crevices of his cell. At last he found it, stowed away in a crack of his cell window that looked into an adjoining sleeping apartment, and which room had recently been occupied nightly by two armed men, who kept watch on Orme, but who vacated the apartment during the day.

On securing the file, Orme commenced a systematic filing on the iron bars of the window mentioned, and had, by persistent efforts, succeeded in nearly severing two of the bars, and entirely cutting through the shackles that secured his feet. His plan was to free himself of his irons, pry off two bars of the window, and when the room mentioned was vacated, get by a stairway to the roof, and then effect his escape. The attempt, however, was frustrated, as follows: —

How the Plan was Foiled.

It was decided to hang the culprit in his cell, there being no jail yard to the prison, and the law provides that hanging must take place within the prison walls.

Late yesterday afternoon Sheriff Miller, accompanied by some other officials, entered Orme’s cell for the purpose of removing him prior to the erection of the gallows. The Sheriff informed him that he would be executed in his cell, and said he had prepared other quarters for him during the remaining short time of his life. When Sheriff Miller stooped down, key in hand, to unlock the chains that bound him, Orme, seeing that all was up with him, told the Sheriff that the use of the key was unnecessary, and giving his legs a shake, off dropped all the chains at once. Orme then showed the Sheriff the filed bars of the window, and related how he intended to escape, and expressed his chagrin at the unexpected interference with his plans. The prisoner was then removed to a cell directly opposite the one he had been confined in, and during the erection of the scaffold he could not only distinctly hear every nail hammered, but could see through the iron grating of his cell door the material used for the scaffold as the workmen carried it by.

The Prison Guarded.

During last night the prison was strongly guarded, both outside and inside, by armed citizens, and men with muskets and pistols were patrolling the streets all night.

Orme Contemplates Committing Suicide.

Last evening Orme was visited by a citizens of Stroudsburg, named Bell, who had shown him numerous kindnesses, and during the interview Orme asked him if, as long as he knew he was to die, it would be wrong for him to commit suicide. Mr. Bell told him it would be very sinful, when Orme, after a moment’s reflection, produced from his clothes a paper containing a considerable amount of morphin [sic], and handed it to his visitor, saying he had kept it to make away with himself, but concluded he would not commit self-destruction. It appears that from time to time morphin had been furnished Orme to make him sleep, but instead of using it he had been carefully keeping it with the intention of taking his own life.

A few days since Orme placed in the hands of Mr. Ridgway, his spiritual adviser, the following document, which has just been made public this morning: —

A Voice from the Prison Cell: or, the Evil of Intoxicating Drinks.

[This was also published under the title “The Wine Cup and the Gallows” -editor.]

STROUDSBURG JAIL, April 17, 1869. — I write this in the hope that it may be the means of arresting the attention, and saving some young man from the path that leads to death and hell — blights and ruins in this world and fixes destiny in the next, amidst the darkness of eternal night: for the sacred volume declares “no drunkard shall inherit the kingdom of God.” Oh! that I could only portray the horrors springing from the first glass, you would shun it as you would the road in which death in its most hideous form was lurking; would to God I had died before I knew the love of passion strong drink can bring to its poor deluded victims, for then I would have had kind friends to weep and think kindly of me, as in solemn silence they gazed into my tomb, but now my earnest prayer to God is that no one who ever knew me may ever hear anything about me. May God in his mercy grant that no more innocent people may suffer on my account.

Oh, young man, by all you hold dear, shun the cup, the fatal cup — if not for your own sake, in God’s name shun it, for the sake of those you hold so near and dear. You may think you are able to take a drink and leave it alone when you wish: let me entreat you, don’t try the experiment, for when it gets hold it rarely ever lets go. It not only destroys you, but friends must suffer also. It may bring a kind and loving mother to an early grave: make an old man of a kind, good father before his time — not to mention brothers and sisters, who must share the sorrow. These things are of daily occurrence; and this is not the worst, for it has incited the mother to murder her innocent babe, the husband to imbrue his hands in the blood of his wife, for whom he would have willingly laid down his own life. Pause! think well before you touch the cup! Remember, you not only venture your own prospects and happiness, but all you hold sacred are involved. Don’t say, I can take a drink and leave off: the chances are against you: and even if they are not, is it right? is it honorable to risk the happiness of others to gratify your own evil appetites? Would to God (that one year ago) I could have seen strong drink as it really is, stripped of all the ornaments thrown over it by those engaged in the traffic; could have seen it as a swift and sure road that was to lead to my present unhappy condition in a felon’s cell, with the prospect of a shameful death. Is it surprising that I would try to save others from the same fate? I know that I have neither the talent nor the education to plead the cause of temperance, but I can tell what the use of intoxicating drinks has brought me to. Can I do less, under the circumnstances, than give a word of advice to some thoughtless ones. Praying (if so great a sinner as I may pray) that God may bless it, and make its truthfulness do what hearing could not be the means of saving some from a drunkard’s end.

For one short moment let your fancy carry you to this lonely cell. You will see me write this with my hands ironed; irons are on my limbs and I am chained to the floor. Do you think what brought me here? I must say, whisy. Is it strange in me to lift a warning voice agianst that which has done me so much harm. Thank God I have not lost all feeling. There are those on the earth, separated from me by “the great waters,” who believe and trust (that whatever I am) I am honest and respected. God forbid that they should ever be undeceived. Oh! is it not hard to pray to God that your dear father and mother, brothers and sisters, your early playmates and friends may never hear about you, or you from them, when one word would be more precious than untold treasure.

A kind word from a stranger is treasured up as something precious, as God knows it is to me. To keep you from such a condition I write this, hoping you will take it in the spirit in which it is given. I write it earnestly and sincerely, trusting that God may bless it to your use. If you are ever tempted to drink think of this advice, and the circumstances under which it is given, and may heaen help you to cast the cursed cup from you. Don’t parley or you are lost. Say no! Stick to it. Once or twice will be enough. Tempers will see that you are firm, and respect you the more for it. Don’t be alarmed at being called a teetotaler. You may be greeted with a laugh or jeer. No matter, you win respect. How often have I wished I could say no, and stick to it, when asked to drink, but my “guess not,” or “think not” was always taken for yes, or if I said no, it was known that I did not always stick to it. A companion who worked by my side was never asked but once, for his “no” meant no! By the power of an emphatic no, when asked to do wrong is the advice of one who has lost all, for the want of a little firmness at first. If I only could tell you all I have lost — lost friends, character, home, all that makes life dear, through drink, by not saying “no,” when asked to do wrong. I could have said it. God gave me understanding. I knew right from wrong but I flattered myself I could go so far, and then let up: now I am lost. God in his mercy grant that this may keep some young man from trending the same path. “Taste not, touch not, handle not,” is the only safe course. Don’t believe in moderate drinking, there is too much danger in it. There is no drunkard living but thought he could leave off when he wished. As I write this I see a fond mother’s face, I hear her last words to me, low and sweet, as she bade her boy God speed, and aid — Be a good boy, shun bad company, and don’t drink.

I see a kind, good father, trying to keep bac the tears, as he gave the same advice, telling me at the same time to “be mindful of God and he would not forsake me.” Alas! all was forgotten, and the result is a felon’s cell, and soon, perhaps, a shameful death. Is it any wonder I should try and warn others? Say you, “that many drink and do not do what I have done?” All true; but none do as I did but what drink, not one. You say a man can take a drink, and not be a drunkard; for God’s sake don’t try it — that is what ruined me. All say at first — “Whisky shall not be my master — I am too much of a man for that.” God help them; how soon they find out that he who said, “Wine is a mocker, strong drink is raging and that he that is deceived thereby is not wise,” knew moreabout it than they. Let a man write all his lifetime and he can utter no greater truths; it mocks all our hopes, blunts all the sensibilities and kind feelings that God has given us, and sinks us lower than the beasts that perish; whereas God made us in his own image. Is it not a mocker? It has ever done harm. The first recorded instance is that of Noah, the only man God saw fit to save with his family, when he destroyed the world. How sadly was he mocked by it, cursing his own son. There has always been a curse with it; the Bible is full of warnings against it. For God’s sake heed them, and “if sinners entice thee, consent thou not.” Would to God that I could put on this paper what I feel.

I think some one would pause before taking that which steals away the senses. But my thoughts wander not where I want them; not to scenes of drunkenness and dissipation but to home — home! Would to God I could banish it from my mind. To-night I am a boy again; I see home as plainly as ever — a kind father, a dear mother, brothers and sisters, all rise before me, not only once, they are always with me now. Even in sleep I see them; pleasant thoughts you say. Oh! God, if I could only get rid of them. I think I could dwell on any others with some degree of comfort, to what I now feel; yes, even on the shameful death I am condemned to die; anything, but what I have lost; lost through drink.

Give an ear to this advice; it is the advice of a dying man — dying in his early manhood, through the accursed cup that “biteth like a serpent.” Think of your friends now, lest the time come when the thought of them will be worse than a scorpion’s sting. Oh! if you see any one treading the downward path, that leads to death and hell, speak kindly to him; you know not the power of a kind word. I do not forget one who has spoken kindly to me since I have been here: how heartily I think of them; a kind word first led me to hope that He who hates sin might yet be merciful to the sinner. I know you all hate the crime that brought me here; but when you saw I had none to speak kindly, though hating my great sin, you pitied me, a poor, wretched sinner, and showed me that mercy, divine mercy, could even reach one so vile.

Oh! young men of Stroudsburg — most of you have seen me, most of you have spoken kindly to me, and have acted as well as spoken. The offer of a book or a paper may be little to you, but to me it was a great kindness. Oh! do me the greater kindness still — take my advice kindly; it comes from a criminal, it is true, but my whole heart goes with it. It ought to be the more effective because coming from one who has run the course and has experienced its terrible results. I might tell you more of what I have seen whisky doing to its dupes, but my article would be too long. I close, giving you the advice a good mother gave me — “Keep out of bad company, and don’t drin.” Don’t let this pass unheeded, as I did. You see what it has brought me to. God keep all that read this in the right path, is the prayer of one who, for the sake of loved ones, prefers to sign himself,

Charles Orme.

He Bears an Assumed Name.

It will appear from the following letter that Orme is an assumed name. —

PRISON CELL, Aug. 7, 1869 — Mr. Martin

Sir. —

My reticence in relation to my connection I may have had with any person in this country, business or otherwise, arises entirely from the fact that I have shamefully abused great privileges which they have granted me; that I do not wish their names to figure in connection with mine. Moreover, any revelations of this kind would only be the means of making known to those that are near (and God only knows how dear to me), my disgraceful end.

Yours, &c.,

Charles Orme.

The Instrument of Death.

The scaffold is erected in the eastern extremity of the cell recently occupied by the prisoner, and is a rather primitive looking affair, with a drop of about four feet. It consists of two upright posts and a cross beam, to which is affixed the rope and a drop made something after the model of a panel of a dining-table.

The Last Night.

Orme passed the night quietly, and was with his spiritual adviser until about ten o’clock, when he was left alone, but a strong guard remained in the entry near the cell door. He rose at an early hour this morning and partook of a light breakfast, consisting of coffee, eggs, &c. He says he slept during a portion of the night, but complained of a severe headache.

Preparing for Death.

About nine o’clock this morning the Rev. Mr. Ridgway administered the sacrament to the dying man, during which Orme was very devout and reverential. He then proceeded to take a bath in a tub or bucket of water which was placed in his cell, after which he deliberately commenced to dress himself for the terrible ordeal which in a few minutes he was to pass through.

Visitors to the City.

Before eleven o’clock Stroudsburg, particularly in the vicinity of the jail, presented quite a holiday appearance. Many hundreds of persons surrounded the jail, and dozens of vehicles of all kinds formed the cordon around the anxiously expectant populace, many of whom came for miles to only look at the blank walls of the jail. All the taverns and saloons were closed during the day by order of the authorities.

The Cell

Where the execution took place is about twenty feet square, with a ceiling fifteen feet in height, affording sufficient altitude for the erection of the gallows.

The Time of Death Approaching.

Shortly before eleven o’clock Mr. Pearce, the Presbyterian minister of the Delaware Water Gap, entered Orme’s cell and engaged in earnest prayer, both the condemned man and the clergyman kneeling. Sheriff Mervine and the Rev. Mr. Ridgway then entered the cell, and Orme again partook of the Sacrament with Mr. Ridgway. sheriff Mervine then informed Orme that his time on earth was nearly ended.

Orme expressing his readiness, he was escorted from his cell across the corridor to the place of execution without parade or ceremony. The cell was crowded to excess with jurors, deputy sheriffs and officials generally, and was uncomfortably hot, there not being the least ventilation.

At theGallows.

Orme entered the cell at five minutes of eleven o’clock, and proceeded up the rude steps of the scaffold with the greatest firmness and self-composure. He was dressed in a black frock coat, black pants and white shirt, and wore no vest. His thick black hair was well combed, and he made a very presentable appearance. The sheriff and the two ministers both ascended the scaffold after Orme, and after the latter was seated the sheriff read the death warrant, prefacing the same with a few remarks intended to cheer the dying man.

The Prisoner’s Speech.

Orme was then asked if he had anything to say, when he addressed those present in a perfectly cool and collected manner, as follows: —

I hardly know what to say, or rather, how to say anything as I would like. I protest in the first place, against my trial. I know that I was convicted on false evidence, and I am entirely innocent of murder, and God forbid that I should lie at a time like this. I trust in Christ, and am sorry for all crimes I have done, but I did no murder. The evidence was false. I don’t like to say anything against the people of Monroe county, for some of them have been very kind to me. I came here a stranger, and was told to hope in Christ, but was falsely convicted.

Thomas Brodhead made a statement on the night of the murder, and he is considered a gentleman of truth, and he made the same statement three times. After my arrest I was taken to the Water Gap to be identified by him, and he made a different statement. I think the District Attorney should have put both statements in evidence. Before the trial I had no friends; all were against me. I was put here and chained and never got a hearing. I got no change of clothing, not even a shirt, and I had to burn the vermin out with a candle.

At this time Sheriff Mervine interrupted Orme by saying, “Was not that before the trial, Charles?” Orme replied that it was, and continued —

I would like to direct attention to Thomas Broadhead’s evidence. He said I had to go back with him, and said Brooks was willing, and I told him not to go. He said he saw Brooks throw some money over the wall, and while stooping down he heard his brother say “Don’t shoot,” and on looking up saw Brooks pointing a pistol at his brother, and on wheeling around Brooks shot Theodore. After that he said he stooped down to pick up something rolled up like a little bill, and says he saw it was a two dollar bill, and swore to the number. Yet he never saw the bill, for I had not stolen it.

The prisoner the proceeded, in a sort of rambling manner, to say he knew nothing of the murder, and threw his pistol away while Thomas and himself were struggling, for fear he might shoot him. He said that Thomas struck him with a stick. Judge Barnard said that Thomas Brodhead’s evidence was not disputed, but after the trial he might have erred, and if he had said this to the jury, the verdict might have been different. He said he did not like to complain of the jury, but he thought he was very badly treated. He praised his counsel highly, and said he could die knowing that no man could say that he shot Theodore Brodhead.

An Interruption.

At that part of Orme’s speech, in which he reflected on his treatment in jail before his trial, ex-Sheriff Henry, who had charge of him at that time, with exceeding bad taste and want of delicacy, advanced from the crowd to the foot of the scaffold, and, addressing the prisoner familiarly as “Charley,” asked him some question about his treatment and his case. Orme answered the question, when ex-Sheriff Henry asked others, and the two got into quite a controversy, which lasted until Mr. Henry was asked to stop. This matter was singularly inappropriate to the solemnity of the occasion. Such a scene has seldom if ever occurred at an execution before this, and should not have been permitted by Sheriff Mervine.

A Last Hope.

Immediate preparations for the execution were then made, when the Rev. Mr. Ridgway stated that Judge Barnard had notified him that he thought it would be proper to hold off the execution until the arrival of the one o’clock train, as it might possibly bring a reprieve from Governor Geary. The Sheriff, at first, did not seem to favor the idea, but Mr. Ridgway pressed it, and Orme, himself, turned to him and said, “Do grant me this short respite, Sheriff? It is the last favor I shall have to ask of you.”

A Short Respite.

The Sheriff, after some hesitation, consented, and the prisoner, who was just about being launched into eternity, was conveyed from the gallows back to his cell, while the spectators all retired from the building. Orme spent the time allotted him in praying and writing notes of thanks to his spiritual advisers and others, and the train arriving, with no reprieve, he was again taken from his cell.

On the Drop Again.

At twenty-five minutes past one o’clock Orme again ascended the scaffold.

The Execution — Orme Twice Hanged.

The Rev. Messrs. Ridgway and Pierce prayed with him until quarter of two o’clock, when the white cap was pulled over his head, and his arms and legs were pinioned with strips of muslin.

Orme stood firm, and moved his lips in prayer with half audible voice, while the Sheriff and ministers retired from the scaffold, and everything being in readiness, the drop fell, and to the intense horror of those huddled together in the cell, the rope broke, and Orme fell to the ground. He was picked up quickly in his half-strangled condition and helped upon the scaffold, when another rope was adjusted, amid a scene of sickening excitement, and again the drop fell and the body of the condemned man was dangling in the air.

The breaking of the rope caused a nervous feeling, which resulted in the noose being badly adjusted, and when the body fell the neck was not broken, and the poor wretch writhed and struggled fearfully. His contortions were heart-rending, and he died a slow death of strangulation. The whole scene was a most revolting one, and will never be forgotten by those who were present. This is the first execution that ever took place in Monroe country, which may be partially the reason for the bungling manner in which it was done.

On this day..

- 979: Gero, Count of Alsleben - 2020

- 1264: Not Inetta de Balsham, gallows survivor - 2019

- 1853: Hans McFarlane and Helen Blackwood, married on the scaffold - 2018

- 1944: Eliga Brinson and Willie Smith, American rapists abroad - 2017

- 1849: Konrad Heilig and Gustav Tiedemann, Baden revolutionaries - 2015

- 1838: The slave Mary, the youngest executed by Missouri - 2014

- 1703: Tom Cook, Ordinary's pet - 2013

- 1908: Khudiram Bose, teenage martyr - 2012

- 1828: William Corder, for the Red Barn Murder - 2011

- 1916: Private Billy Nelson - 2010

- 1997: Zoleykhah Kadkhoda survives stoning - 2009

- 1978: Antonina Makarova, Nazi executioner - 2008

Among the more militant types excited to wrath against Kingsford was

Among the more militant types excited to wrath against Kingsford was

This

This