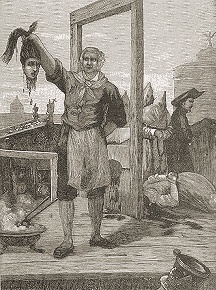

On this date* in 1947, the only president of the world’s only Kurdish state was hanged with two aides in Mahabad, the Iranian city that had been the capital of his nascent country.

Ground between the maneuvers of much more powerful states — the stereotypical fate of the Kurds — Qazi Muhammed‘s endgame begins not in mountainous northwest Iran where he declared the short-lived Republic of Mahabad (alternatively, Mehabad), but in Berlin, where a distant dictator had hurled Europe’s great powers into war.

Ground between the maneuvers of much more powerful states — the stereotypical fate of the Kurds — Qazi Muhammed‘s endgame begins not in mountainous northwest Iran where he declared the short-lived Republic of Mahabad (alternatively, Mehabad), but in Berlin, where a distant dictator had hurled Europe’s great powers into war.

The contest for influence in Middle East and its lifeblood of oil for the modern mechanized army forms a crucial sidebar to World War II’s European chessboard, and the unpredictable collisions between rival empires and competing anticolonial interests made many strange bedfellows.

Two months after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, British and Soviet troops jointly seized Iran from its potentially pro-German ruler — securing both oil resources** and a precious route for sending American supplies to Russia’s desperately pressed defenders.

Kurds were very far from Stalin or Churchill’s calculation, but the moment also offered a power vacuum permitting de facto Kurdish self-rule in a narrow band straddling Soviet and British occupation zones.

As the war drew to a close, erstwhile allies began girding for the Cold War — and the disposition of Iran was a dress rehearsal. Moscow was keen to maintain influence in that country’s north, and to that end encouraged Iran’s Azerbaijani region to break away as an independent state — which it did in December 1945. The Kurdish Republic of Mahabad followed suit on January 22, 1946 (a date still commemorated by Kurdish activists) with Qazi Muhammed as president. Although the Mahabad Republic is sometimes characterized as “Soviet-backed,” or even a Soviet puppet, that might be a better description of its hopes than its reality.

Mahabad may have represented the national dream for Kurds, but it was a small pawn to the Soviets, easily sacrificed when its position became untenable. Moscow’s priorities were elsewhere, and this was the brief window when America was the only nuclear power: the Red Army was (diplomatically) forced out of Iran and the breakaway Republics reoccupied by the western-backed Iranian government. And Mahabad, a statelet founded by a middle class party with only limited backing from tribal chiefs, required Soviet support to have any hope of holding up.

Seeing where the wind was blowing, the Kurds submitted in December 1946 to the advancing Iranian army without a hopeless fight, but Muhammed refused on his honor to flee, hoping to placate the Iranians.

For all its inadequacies, Mahabad was the only Kurdish state of the 20th century, and Qazi Muhammed its founder and only president. That has earned him a place of honor in the crowded pantheon of Kurdish martyrs.

After a military court had him hanged, leadership of the Kurdish struggle passed to Mustafa Barzani, whose refugee guerrillas had made declaration of the Kurdish state a possibility in the first place.

In a biography of Barzani written by Barzani’s son, the Kurdish captain describes his last meeting with the president — and if the manifest interest of the reporting parties colors our presumption of its literal authenticity (journalist Jonathan Randal, for instance, reports that Barzani never held Mohammed in high regard), it likewise underscores the place of this day’s victim in the Kurdish mythology.

I went to Qazi Mohammed and asked him what he personally intended to do. He said that he intended to sacrifice his life to prevent bloodshed in Mahabad, that he would surrender to the Iranian forces, and that he had sent an emissary to General Hamayoni in Miyandoab informing him of his decision. He broke down in tears as he continued: “Never rely on anyone but your own group. All those who took the oath of allegiance have betrayed us and are rushing to prove their loyalty to the Iranian forces. Beware of the tribal chiefs who would target you if they could. I hope that you will leave Mahabad as soon as youc an to avoid confronting the Iranian forces.”

…

I insisted that he go with us [to Iraq], and pledged my word of honor that I would sacrifice my life and the lives of all who were with me to defend him, because he was the symbol of our nation. I told him that my advice to him was not to trust Iranian promises. It would be painful to see the first president of the Republic of Kurdistan fall into enemy hands.

In tears, Qazi Mohammed rose and hugged me, saying, “I pray God will give you strength and protect you. May my sacrifice spare the citizens some of their affliction and mitigate the terror and vengeance.” Then, he pulled a flag of Kurdistan from his pocket and gave it to me and said: “This is the symbol of Kurdistan. I give it to you as a token of trust in your honor, for I think you are the bes man to keep it.”

The Encyclopedia of Kurdistan has an excellent entry on Mahabad’s straitened political situation, as well as a good article on the background of tribal politics in the years prior to World War II.

* Some sources report March 30; the small hours in the morning of the 31st seems to have the plurality of scholarship.

** Although Baku was a much more important source of oil for the USSR.

On this day..

- 1984: Ryszard Sobok

- 1536: Michael Seifensieder, Hieronymus Kals and Hans Oberecker, incriminating abstention

- 1794: Madame Lavergne and Monsieur Lavergne, united in love

- 1832: James Lea and Joseph Grindley, arsonists

- 1777: James Molesworth, in the words of the Founding Fathers

- 1843: A bunch from Heage hanged

- 1949: Dr. Chisato Ueno, because life protracted is protracted woe

- 1923: Konstanty Romuald Budkiewicz, Catholic priest in the USSR

- 1312: Pierre Vigier de la Rouselle, Gascon

- 1984: Ronald Clark O'Bryan, candyman

- 1856: William Bousfield, Calcraft'd

- 2001: Mariette Bosch, love triangulator

God is not the creator of man; but man is the creator of a God gathered together from nothing.

God is not the creator of man; but man is the creator of a God gathered together from nothing.

Like his onetime lieutenant

Like his onetime lieutenant  “Finally, the executioner, Samson, said to Monsieur Le Breton that there was no way or hope of succeeding, and told him to ask their Lordships if they wished him to have the prisoner cut into pieces. Monsieur Le Breton, who had come down from the town, ordered that renewed efforts be made, and this was done; but the horses gave up and one of those harnessed to the thighs fell to the ground. The confessors returned and spoke to him again. He said to them (I heard him): ‘Kiss me, gentlemen.’ The parish priest of St Paul’s did not dare to, so Monsieur de Marsilly slipped under the rope holding the left arm and kissed him on the forehead. The executioners gathered round and Damiens told them not to swear, to carry out their task and that he did not think ill of them; he begged them to pray to God for him, and asked the parish priest of St Paul’s to pray for him at the first mass.

“Finally, the executioner, Samson, said to Monsieur Le Breton that there was no way or hope of succeeding, and told him to ask their Lordships if they wished him to have the prisoner cut into pieces. Monsieur Le Breton, who had come down from the town, ordered that renewed efforts be made, and this was done; but the horses gave up and one of those harnessed to the thighs fell to the ground. The confessors returned and spoke to him again. He said to them (I heard him): ‘Kiss me, gentlemen.’ The parish priest of St Paul’s did not dare to, so Monsieur de Marsilly slipped under the rope holding the left arm and kissed him on the forehead. The executioners gathered round and Damiens told them not to swear, to carry out their task and that he did not think ill of them; he begged them to pray to God for him, and asked the parish priest of St Paul’s to pray for him at the first mass. However, Reagan’s reprieve bought him just enough time to live to see a California Supreme Court decision temporarily halting executions, which was followed by the US Supreme Court

However, Reagan’s reprieve bought him just enough time to live to see a California Supreme Court decision temporarily halting executions, which was followed by the US Supreme Court  A teacher by training and a member of the country’s powerful namesake tribe,

A teacher by training and a member of the country’s powerful namesake tribe,

Gerald Eugene Stano’s problems didn’t end with his new life with his adoptive parents; instead, he continued to develop a series of problems that would follow him, shaping his outlook on the world forever, and likely providing him with the excuses he needed to justify his actions later in life.

Gerald Eugene Stano’s problems didn’t end with his new life with his adoptive parents; instead, he continued to develop a series of problems that would follow him, shaping his outlook on the world forever, and likely providing him with the excuses he needed to justify his actions later in life.

Mastro Titta was given an official residence, and at the end of his term, he was handsomely rewarded with a pension for his service — 30 scudi per year. His final executions were carried out on 17 August 1864, wearing his traditional red cloak (now on display at the

Mastro Titta was given an official residence, and at the end of his term, he was handsomely rewarded with a pension for his service — 30 scudi per year. His final executions were carried out on 17 August 1864, wearing his traditional red cloak (now on display at the