On this date in 1765, Boston patriots lynched the merchant designated as the imperial taxman. They only did so in effigy, but the “execution” scared him permanently off the job while also making a gallows-tree into one of the earliest symbols of American independence.

One of the key pre-revolution irritants for the future United States, the 1765 Stamp Act imposed taxes in the form of stamp duties on a variety of printed products, for the purpose of funding the British army deployed to North America. It was a levy long familiar to London lawmakers but it sent the colonies right around the bend, and since the colonies sat no Member of Parliament who could flip an official wig it also popularized the classic revolutionary slogan about “taxation without representation.”*

Enacted in the spring of 1765 and due to take effect in November, the Stamp Act drew immediate outrage in the colonies and especially in that hotbed of subversion, Boston.

There, Andrew Oliver, scion of a shipping magnate clan, was tapped to collect the levy. It figured to be just the latest in a series of lucrative state appointments. How was he to know in advance that this particular legislation would unleash the crazies? Perhaps he should have given more heed to the publication of ominous warnings over the roster of tax collector names.

Boston Post-Boy, August 5, 1765

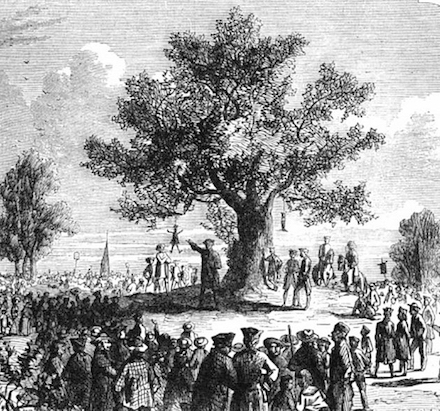

On the morning of Wednesday, August 14, a crowd of irate Bostonians mobbed the corner of Essex Street and Orange Street (present-day Washington Street) and upon a large elm tree strung up an effigy of Oliver alongside a boot — the footwear comprising a second, punny, effigy of the Stamp Act’s sponsor the Earl of Bute.

“What greater Joy can NEW-ENGLAND see,” ran the menacing note pinned to the mannequin, “Than STAMPMEN hanging on a Tree!” As is clear from the following newspaper account, versions of which circulated widely in New England, these were no mere theatrics but a very proximate physical threat; even the elm’s property owner dared not take down the provocative display for fear that the crowd would pull down his house. Likewise taking the better part of valor, Oliver pledged to anti-tax colonists that he would not take the office, and he kept his word.**

Providence Gazette, August 24, 1765

After this triumphant debut, the elm in question became a common rallying-point for the hotheaded set, a frequent stage for speechifying, rabble-rousing, and fresh instances of popular justice all further to the patriot cause until, as Nathaniel Hawthorne put it, “after a while, it seemed as if the liberty of the country was connected with Liberty Tree.” Of course, it’s all a question of whose liberty; a Tory gloss on this deciduous republican made it “an Idol for the Mob to Worship; it was properly the Tree ordeal, where those, whom the Rioters pitched upon as State delinquents, were carried to for Trial, or brought to as the Test of political Orthodoxy.” When besieged in Boston in 1775-1776, British Tories cut the damned thing down, so for subsequent generations it was only the Liberty Stump.

“The Colonists Under Liberty Tree,” illustration from Cassell’s Illustrated History of England, Volume 5, page 109 (1865)

The Liberty Tree is commemorated today at its former site, and forever in verse by revolutionary firebrand Thomas Paine.

In a chariot of light from the regions of day,

The Goddess of Liberty came;

Ten thousand celestials directed the way,

And hither conducted the dame.A fair budding branch from the gardens above,

Where millions with millions agree,

She brought in her hand as a pledge of her love,

And the plant she named Liberty Tree.The celestial exotic struck deep in the ground,

Like a native it flourished and bore;

The fame of its fruit drew the nations around,

To seek out this peaceable shore.Unmindful of names or distinctions they came,

For freemen like brothers agree;

With one spirit endued, they one friendship pursued,

And their temple was Liberty Tree.Beneath this fair tree, like the patriarchs of old,

Their bread in contentment they ate

Unvexed with the troubles of silver and gold,

The cares of the grand and the great.With timber and tar they Old England supplied,

And supported her power on the sea;

Her battles they fought, without getting a groat,

For the honor of Liberty Tree.But hear, O ye swains, ’tis a tale most profane,

How all the tyrannical powers,

Kings, Commons and Lords, are uniting amain,

To cut down this guardian of ours;From the east to the west blow the trumpet to arms,

Through the land let the sound of it flee,

Let the far and the near, all unite with a cheer,

In defence of our Liberty Tree.

* Visitors to the U.S. capital of Washington D.C., whose 700,000 residents cast no votes in the Congress they live cheek by jowl with, can find this familiar grievance right on the city’s license plates.

** How far this surly bunch was prepared to go on August 14, 1765, one can only guess at; however, in later years, there would be several instances of Bostonians tarring and feathering various tax collectors. These guys did not do civility politics.

On this day..

- 1954: Nikos Ploumpidis, Greek Communist

- 2018: Carey Dean Moore

- 1944: Lucien Natanson

- 1878: Ivan Kovalsky, nihilist martyr

- 1679: John King and John Kid, Covenanters

- 1793: Walter Clark, hanged women's father

- 1480: The Martyrs of Otranto

- 1820: Amasa Fuller, the Indiana hero

- 1949: Husni al-Za'im, Syrian president

- 1860: John Moyse, the Private of the Buffs

- 2004: Dhananjoy Chatterjee, the last hanged in India ... for now

- 1936: Rainey Bethea, America's last public hanging

One of the towering figures of France’s

One of the towering figures of France’s