On this date in 1667, the uncle of the sessei — think Chief Minister or Grand Vizier — of the Ryukyu Kingdom covering the island chain south of Japan was beheaded for a diplomatic scandal.

The Ryukyu Kingdom was a weak state that made its way in vassalage to burlier neighbors, including mainland China to its west and the Japanese feudal state Satsuma to the north. Satsuma had defeated Ryukyu in war in the early 17th century, and according to Angela Schottenhammer (The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration) Satsuma dominated Ryukyu to the extent of providing it gold, silver, and tin — not native to Ryukyu — for the latter to send as offerings to China.

The primary interest of Satsuma lay in trade with China … Since Satsuma did not have direct contacts with China and [China] officially did not want to have any relation with Satsuma, Satsuma controlled the lucrative tribute trade activities of the Ryukyus with China backstage. As far as we can tell from the available documents, Satsuma issued a series of orders to the Ryukyuans to conceal their relations with them from the Chinese, especially during the times of a Chinese investiture mission staying in Ryukyu, in order to successfully continue to obtain Ryukyuan products. Ryukyuan tribute missions were secretly used by Satsuma to obtain highly prized Chinese products for resale in Japan. The Satsuma-Ryukyuan relationship, like Robert Sakai describes, “was maintained side by side with the tributary relationship between China and Ryukyu”. This practice was carried on in the Qing dynasty. It is clear that the Ryukyus contituted an asset to Satsuma as an economic bridge between China and herself.

This trilateral relationship will help to explain the beheadings that occasion this post.

Our man Chatan Chocho, a former member of the Ryukyuan governing council, was chagrined to discover in 1665 that the emissary Eso Juko, recently dispatched from Ryukyu to China, had been ambushed by so-called “pirates” who were actually Chatan’s very own retainers in disguise. They made off with the gold offerings that were bound for the young Chinese emperor.

Needless to say this was an offense against statecraft and commerce far more serious than mere brigandage. Satsuma investigated it with al the urgency due its economic bridge with China.

It’s known as the Chatan Eso Incident, which tells you that Chatan’s attempt to bury his own connection to the crime by having those involved murdered privately did not succeed. In its capacity as the Ryukyuan boss, Satsuma ordered both Chatan and Eso condemned to death, and delivered them to Ryukyu to execute the sentence. Their children were scattered to outlying islands in internal exile. (It’s not clear to me whether Eso, the envoy who got robbed, was viewed as actively complicit in the heist, or if his execution flowed from the failure to complete his mission or a general policy of maximal due diligence.)

* I’m reporting this, with trepidation, per the dates in Wikipedia entries. I have had no luck at all tracing a primary source for this date; nor even the original calendar register to confirm whether “July 11” is indeed a correct Gregorian rendition. The best that I can report is that, per this calculator that served us well in our Torii Suneemon post, July 11 corresponds to 20th-21st Satsuki (the fifth month) of the Japanese lunisolar calendar, and 1667.5.21 is the date reported in the Chinese Wikipedia entry for the incident. That is very thin sourcing indeed; there’s ample scope for error here.

On this day..

- 1958: Peter Manuel, the Beast of Birkenshaw - 2019

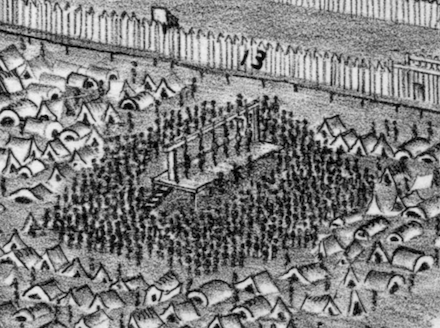

- 1864: The Andersonville Raiders - 2018

- 1408: Konrad Vorlauf, Vienna Burgermeister - 2017

- 2006: Derrick O'Brien, for murdering Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Pena - 2016

- 1890: Edward Gallagher, "none of your damned business!" - 2015

- 1789: Francis Uss - 2014

- 1644: Joost Schouten, LGBT VOC VIP - 2013

- 1952: Chester Gregg - 2012

- 1780: Five for the Gordon Riots - 2011

- 1892: Ravachol, anarchist terrorist - 2010

- 1836: Louis Alibaud, failed regicide - 2009

- 472: Anthemius, twilight emperor of Rome - 2008

Gregg

Gregg