On an unknown date thought to be approximately June of 1971, American photojournalists Sean Flynn and Dana Stone were executed by Communist captors in Southeast Asia.

Flynn is the big name of the pair,* literally: a former actor, he wasn’t in like his superstar father Errol Flynn. After trading on his prestigious name for a few silver screen credits, Sean grew bored of Hollywood and pivoted into a career in wanderlust — trying his hand as a safari guide and a singer before washing up in Vietnam where the action was in January 1966.

He made his name there as a man who would find a way to snatch an indelible image out of war’s hurricane, even at the risk of his own life.

One of Flynn’s photos: A captured Viet Cong being tortured. (1966)

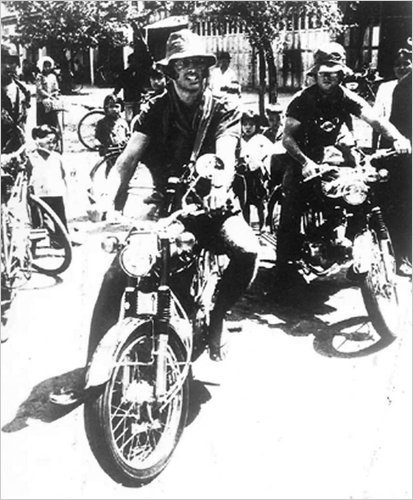

On April 6, 1970, Flynn and fellow risk-seeking photojournalist Dana Stone hopped on rented motorbikes bound for the front lines in Cambodia. It was a last mission born of their characteristic bravado — all but bursting out of the frame astride their crotch rockets in the last photo that would become their epitaph. They were never seen again; having apparently been detained at a Viet Cong checkpoint, it’s thought that they ended up in the hands of Cambodian Khmer Rouge guerrillas and were held for over a year before they were slain by their jailers.

Flynn (left) and Stone mount the bikes for their lethal assignment. This is the last picture ever taken of them.

Sean’s mother, actress Lili Damita, spent years seeking definitive information about his fate, without success. Dana’s brother, John Thomas Stone, joined the army in 1971 reportedly with a similar end in mind; he was killed by friendly fire in Afghanistan in 2006. The prevailing conclusion about their fate arrives via the investigation of their colleague and friend, Australian journalist Tim Page — a man for whom memorializing the journalists who lost their lives during the Vietnam War has been a lifelong mission.

Though Flynn’s and Stone’s guts are undeniable, not everyone appreciated their methods. “Dana Stone and Sean Flynn [son of the Hollywood actor, Errol Flynn] were straight out of Easy Rider, riding around on motorcycles carrying pearl-handled pistols. Cowboys, really,” said fellow photog Don McCullin. “I think they did more harm than good to our profession.”

* He’s not to be confused with present-day actor Sean Flynn — that’s our Sean Flynn’s nephew. (Sean the nephew was named for Sean the uncle.)

On this day..

- 1764: John Ives, spectator turned spectacle - 2020

- 1895: John Eisenminger, forgiven - 2019

- 1900: Guzeppi Micallef, Maltese felon - 2018

- 1730: Sally Bassett, Bermuda slave - 2017

- 1940: 32 innocent Poles - 2015

- 1962: Henry Adolph Busch, Psycho - 2014

- 1884: Charles Henry, iced in the Arctic - 2013

- 1662: Potter, bugger - 2012

- 1879: John Blan, panicked - 2011

- 1671: Stenka Razin, Cossack rebel - 2010

- 1832: Not Javert, spared by Jean Valjean - 2009

- 1997: Henry Francis Hays, whose crime cost the Klan - 2008

The child of a poor peasant’s family, Nim was a gifted young state worker who studied in Paris in the 1950s, where he met several future Khmer Rouge leaders.

The child of a poor peasant’s family, Nim was a gifted young state worker who studied in Paris in the 1950s, where he met several future Khmer Rouge leaders.