(Thanks to Richard Clark of Capital Punishment U.K. for the guest post, a reprint of an article originally published on that site. The images accompanying this post are also provided by Mr. Clark. -ed.)

Sandra Smith was the last woman to be hanged in South Africa (with her boyfriend Yassiem Harris).

Background.

Sandra Smith was a 22-year-old coloured woman (official South African designation during the apartheid era) who was married to a trawlerman called Philip and had two small children. Philip spent long periods at sea and sent money back for Sandra and the children. She began having an affair with Yassiem Harris, who was 3 years her junior, in the autumn of 1983 and soon they were deeply in love. Harris had been involved in crime since the age of 13 and had convictions for theft and fraud and was also a drug user. Philip found out about the affair from his neighbours and in March of 1986, he finally threw Sandra out. She and Harris now began living together in a rented apartment but soon the money that Philip used to give her ran out and their finances became tight.

The crime.

To make ends meet, they tried renting video recorders from shops and then selling them but this didn’t net them any real money. Harris, who was unemployed, also spent time hanging about outside a girl’s school and got to know some of the girls, including Jermaine Abrahams. He soon found out where she lived and from his conversations with Jermaine, he concluded that her family were quite wealthy.

They hatched a plan to break into the Abrahams’ family home and steal her mother’s jewelry and anything else of value. Harris had also found out that her parents left for work at 7.00 a.m. in the morning and she left for school about 7.40 a.m.

The victim, Jermaine Abrahams.

Smith and Harris arrived at the house about 7.30 a.m. on September the 1st, 1986, and Harris was let in by Jermaine on the pretext of him wanting to use the telephone. They tied Jermaine up but were disturbed by someone knocking at the door. She started to shout for help and struggle so they then tried to strangle her with a dish cloth. Harris now fetched a knife from the kitchen and repeatedly stabbed Jermaine in the neck. Amazingly, she didn’t die from her injuries and managed to get to her feet and stagger a few paces before collapsing. Harris carried Jermaine to her parents bedroom and made her show him where the jewelry and valuables were kept. He wrapped the poor girl in a duvet and then cut her throat, leaving her to bleed to death. He and Smith collected up what they wanted and then left the house.

Two weeks later, while Smith was being questioned by the police regarding the video scam, she surprised the interviewing officer by confessing to the killing of Jermaine. “I wouldn’t have been able to live with it,” she said. In her statement she told the police, “He pulled the scarf tight across her mouth and then cut her throat.”

On the 15th of September 1986, Sandra Smith was formally charged with the murder and 5 days later Harris was arrested and also charged with it.

Trial.

At their committal hearing at the Mitchell’s Plain Magistrates’ Court on the 23rd of September, they pleaded guilty to murder, alternatively to culpable homicide, and to stealing R2,000 worth of jewelry.

They were tried together at the Cape Town Supreme Court on December the 1st, 1986, before Mr. Justice Munnik, the Judge-President of the Cape Court, and two assessors. South Africa did not use the jury system, although its court proceedings were based upon British law, but instead a system of a judge and assessors. Both were represented by counsel and both attempted to shift the blame on to the other. Smith maintained that Harris had done the actual killing and Harris claimed to have been dominated by Smith, although they both admitted being present during the murder.

Sandra Smith was embarrassed by the revelations of her sex life with Harris in court and seemed at times more concerned with these than the fact that she was on trial for her life.

Having heard all the evidence, Mr. Justice Munnik gave a full reasoned judgement in which he described Harris as “an appalling witness.” He said it was clear that it was Harris who had stabbed the girl and slit her throat to prevent her identifying them. He also rejected Harris’ defence claim that he been dominated by Smith which had been refuted by the psychiatrist giving evidence for the prosecution. He accepted that Smith was demanding but not dominant, and there was no evidence to indicate that she forced Harris to kill Jermaine, nor that she had done anything to prevent the murder. He thus concluded that they were both equally responsible for the crime under the doctrine of “common purpose.” Thus on the 11th of December 1986, they were both formally convicted of the murder of Jermaine Abrahams and with robbery with aggravating circumstances and remanded for sentence.

Eleven days later they were brought back to the court and received the mandatory sentence for murder — that they be hanged by the neck until they were dead. Additionally, Harris received a 10-year prison sentence for robbery and Smith was given seven years for it. Sandra Smith became hysterical when she was sentenced to death and had to be taken struggling and screaming to the cells.

They were transferred to the country’s only death row, at Pretoria Central Prison, a modern facility on the outskirts of the capital where all South African executions were carried out. Their appeals were turned down and the review of the trial transcripts to determine whether to recommend that the state president grant clemency carried out by the Ministry of Justice failed to find any mitigating circumstances. As clemency was not forthcoming, their execution date was set for the 2nd of June 1989. Apparently, only around one in 50 people convicted of homicide were actually hanged at this time, the majority serving a prison sentence.

Execution.

At 6.50 a.m. on that morning, Smith was taken to meet Harris for the first time in over two and a half years. Together with two other men who had been convicted of murder, they were led the 52 steps to the pre-execution room next to the gallows. The death warrants were read to them and they were given the opportunity to say their last words. Their hands were handcuffed behind them and white hoods placed over their heads, these having a flap at the front which was left up until the last moment.

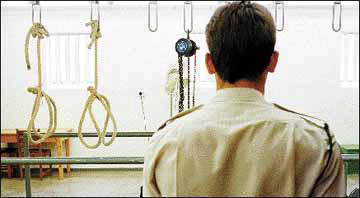

They were now led forward by warders into the large and brightly lit execution room. It was some 40 feet long with white painted walls. They would have seen the gallows beam running the length of the room and the 7 large metal eyes from which the four nooses dangled. (Seven prisoners could and often were hanged at once on this gallows.) The picture shows very much what Smith and Harris would have seen as they were led to the gallows. The chain hoist on the middle metal eye is used for raising the trapdoors after an execution.

They were positioned side by side, on painted footprints over the divide of the trap and held by warders while the hangman placed the nooses around their necks. He then turned down the hood flaps and when all was ready, pulled the lever plummeting them through the huge trapdoors.

They were left to hang for 15 minutes before being stripped and examined by a doctor in the room below. Once death had been certified, the bodies were washed off with a hose and the water allowed to drain into a large gully in the floor. A warder put a rope around each of their bodies and with a pulley lifted them to allow the rope to be taken off. They were then lowered onto a stretcher and placed directly into their coffins before taken to a public cemetery for burial.

Although executions in South Africa were held in private, the procedure was described in detail by the then hangman, Chris Barnard, in an interview before he died. He officiated at over 1,500 hangings there.

South Africa hanged 1,123 people at Pretoria Central prison between 1980 and 1989, Solomon Ngobeni being the last on November 14th, 1989. Surprisingly perhaps, almost all of these were for “ordinary” murders rather than politically motivated crimes and most attracted very little publicity.

According to the South African Department of Correctional Services, two other coloured women were hanged for murder in the years 1969 to 1989, Gertie Fourie, on the 20th of May 1969 and Roos de Vos, on the 12th of December 1986. A total of 14 women were executed between 1959 & 1989, out of a total of 2,949 hangings.

President De Klerk ordered a moratorium on executions in 1990 and capital punishment was abolished altogether by the incoming black government of Nelson Mandela on the 7th of June 1995.

Comment.

We cannot know why Smith and Harris went to the Abrahams’ home while they knew Jermaine would still be there or whether they had actually formed any intention to kill her. Neither of them had any record of violence prior to the murder. My guess is that they panicked when she started to call for help from the person who knocked on the door and they tried to silence her. However, it seems hard to believe that Harris really thought she wouldn’t identify him to the police as soon as they had left and he may well have decided to kill her for this reason. It is claimed that Smith wanted Jermaine dead as she was jealous of her having some sort of relationship with Harris. In any event, Jermaine suffered a horrible and agonising death at their hands.

We cannot know, either, which one of them did the actual killing or whether they both took equal part in it. But there was clear “common purpose” established under law, and there were no obvious mitigating circumstances to allow the state to reduce the sentence on either of them. South Africa had the highest rate of judicial execution in the world during the 80’s so they would surely have known the penalty for murder but like so many people, gave no thought to it until it was too late.

Sadly, it is so typical of the kind of brutal and senseless murder that happens all too frequently and one that led to cruel deaths for three young people.

On this day..