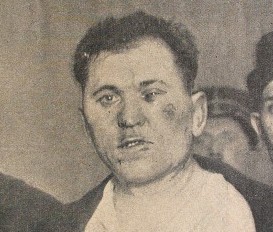

El Salvador campesino Jose Feliciano Ama was hanged in the town square of Izalco on this date in 1932 during a ferocious repression of the peasantry.

In an environment of desperate economic immiseration for nearly all Salvadorans below the landed oligarchy, the heavily indigenous western peasantry rebelled on January 22, 1932 — aided or led by the Communist Party.*

In an environment of desperate economic immiseration for nearly all Salvadorans below the landed oligarchy, the heavily indigenous western peasantry rebelled on January 22, 1932 — aided or led by the Communist Party.*

This fate of this rebellion might be inferred by its historiographical sobriquet, the Salvadoran peasant massacre — or simply la Matanza, the slaughter.

In numerical terms, it ran to well into the tens of thousands, maybe up to 40,000 — indiscriminately visited on peasants of originario complexion in the zone of rebellion, batches of them summarily shot into mass graves they’d been forced to dig for themselves.

In the Pipil town of Izalco, where coffee latifundias dominated the best agricultural land,* up to a quarter of the population was butchered. None of those put to la Matanza were more recognizable nor more vividly recalled than the local rebel leader Feliciano Ama English Wikipedia entry | Spanish), extrajudicially noosed in front of the Izalco church. Today a small plaque in this square honors him as a popular martyr.

* See States and Social Evolution: Coffee and the Rise of National Governments in Central America. An heiress of coffee magnate and former president Tomas Regalado allegedly forced our Feliciano Ama off his lands by dint of brute force.

On this day..

- 1886: The leadership of the Proletariat Party - 2019

- 1591: Agnes Sampson, North Berwick witch - 2018

- 1820: The slaves Ephraim and Sam, "awful dispensation of justice" - 2017

- 1573: Lippold ben Chluchim, scapegoat - 2016

- 1989: Teng Xingshan, butcher - 2015

- 1820: Not Stephen Boorn, saved by newsprint - 2014

- 1656: Joris Fonteyn, anatomized and painted - 2013

- 1697: John Fenwick, bitter - 2012

- 1829: William Burke, eponymous body-snatcher - 2011

- Themed Set: The Medical Gaze - 2011

- 2010: Five for the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman - 2010

- 1953: Derek Bentley, controversially - 2009

- 1853: Nicholas Saul and William Howlett, teenage New York gangsters - 2008

A parade to celebrate the emperor’s birthday may be standard enough fare on the home front, but in a China being

A parade to celebrate the emperor’s birthday may be standard enough fare on the home front, but in a China being