On this date in 1869, two men of the aboriginal Hesquiat nation of Vancouver Island off British Columbia’s Pacific coast were hanged outside their village by the white colonial authorities, on the charge of gratuitously murdering the (again, white) survivors of a shipwreck.

The English-built barque John Bright foundered in a gale just offshore from the location of the eventual gallows in February of that same year, with all aboard lost — including apparently the wife of the captain, their children, and the pretty young English nursemaid who looked after them.* Although within sight of a Hesquiat village also called Hesquiat, the violent surf put the vessel beyond aid.

The tale of a ship lost to the sea soon became in the eyes of Vancouver Island’s European capital city, Victoria, a very different tale of villainous “West Coast savages.” An unprincipled trader named James Christenson was the first to report the shipwreck in Victoria and put about his suspicions that at least some of the John Bright‘s denizens had reached shore alive. His evidence for this claim was seeing several headless bodies. A more generous interlocutor might proceed from this observation to indict the implacable violence of the rough open-ocean surf that would have carried the drowned to shore, crashing through the John Bright‘s timbers and tossing boulders hither and yon.

Instead the most diabolical inferences were immediately bandied as fact, with the city’s preeminent journalist D.W. Higgins categorically broadcasting that the ship’s personnel “were without doubt murdered by the Indians” and whipping political pressure that forced the colonial government into action. The HMS Sparrowhawk was dispatched to investigate with its conclusions so firmly determined that the refusal of the ship’s doctor to endorse a finding of homicide relative to the bodies he examined did not save native canoes from a cannonade meant to force the village to surrender some suspects. In the end the gunboat returned to Victoria with seven new passengers, two of whom wound up on the gallows: a man named John Anayitzaschist, whom some witnesses accused in contradictory accounts of shooting survivors on the beach, and a wretch named Katkeena (or Kahtkayna) who wasn’t even present in Hesquiat Village at the time of the shipwreck. The former man was a factional rival of the Hesquiat chief. The latter “was a simpleton of inferior rank and considered so worthless that not one woman of his tribe would take him as a husband,” according to the Catholic missionary Augustin Brabant, who lived for many years afterward among the Hesquiat people. He seems to have been given over to the executioner because he was disposable.

The case has receive a bit of renewed scrutiny in the 21st century: the British Columbia government issued a statement of regret in 2012, and an empathetic musician composed a string quartet (“Cradle Song for the Useless Man”) in honor of the forlorn Katkeena.

Executed Today comes by the affair via a wonderful 1997 book, Glyphs and Gallows: The Art of Clo-oose and the Wreck of John Bright. Author Peter Johnson weaves the wreck of the John Bright and the legal shambles that ensued with his exploration of native art — including the titular petroglyphs etched into coastal stone by native artists where still they sit to this day.

Executed Today comes by the affair via a wonderful 1997 book, Glyphs and Gallows: The Art of Clo-oose and the Wreck of John Bright. Author Peter Johnson weaves the wreck of the John Bright and the legal shambles that ensued with his exploration of native art — including the titular petroglyphs etched into coastal stone by native artists where still they sit to this day.

Drawn to the story by (accurate) reports of glyphs depicting European ships, Johnson hiked to the petroglyph site at Clo-oose where he sketched and photographed these amazing productions. The glyphs tantalize with the never-consummated possibility that they might directly allude to the John Bright affair, but more than this: in Johnson’s telling, they’re a priceless point of contact offered us by the hand of the artist to a cosmology in the moment before it is irrevocably lost to the tectonic action of European settlement.

Soon after the John Bright affair, things changed on the coast. The Colony of British Columbia joined Confederation, and the Royal Navy no longer sent its gunboats to intimidate worrisome Aboriginals. Settlement occurred, law and order prevailed, the potlatch and the totem poles were taken away. Disease forced a good many Natives to sanitoria, and Native children were sent to the residential schools run by Roman Catholic and Anglican missionaries. Families were disconsolate. The soul of a race was broken, and the moss-wet forest slowly reclaimed the longhouses and the welcome figures of a once proud people. A whole culture was literally on the brink of being wiped out completely. And then, from the very edge of oblivion, the elders began to retell their stories. It was these bits of remembered tales, called up from a desperate soul’s interior like images forced onto stone, that would enable everything to begin again.

The motive for metaphor is the motive to create a story: it is the artistic drive. The impulse to use symbols is connected to our desire to create something to which we can become emotionally attached. Symbols, like relationships, involve us with deeply human attributes. Raven and Bear can speak to us directly. I can smile at the glyph of a seal, with its curious smiling head poking just above the water, and I am filled with wonder at the image of a bird carrying a small child or a bodiless head. A symbols is at once concrete, palpable, and sensual — like a rose. At the same time, it reaches beyond itself to convey an idea of beauty, of fragility, and of transience. The great thing about art is that it continually forces us to see new sets of resemblances. Those long-gone artists who created the petroglyphs at Clo-oose used two sets of symbols — their own and those of nineteenth-century Western Europeans — in order to depict a vignette that was firmly grounded in their point of view. Like the carvers of the Rosetta Stone, they wisely used sets of metaphors and imaginative icons against materialist images of nineteenth-century commercial technology. Unlike the Rosetta Stone, however, the petroglyphs of Clo-oose do not use one set of images to explicate the other; the petroglyphs of Clo-oose are stunning because they incorporate one set of images into the other. Like a series of lap dissolves in modern film, we are drawn to ponder one story while at the same time being faced with the jarring reality of another … They are rich metaphors of the interior world of Native spirituality and history, and they have been juxtaposed with metaphors of European conquest. As such, they are eloquent indeed.

It is impossible to completely crack the codes of the sailing-ship glyphs of Clo-oose because the meaning of the Native spiritual images cast upon the rocks on that lonely shore has died with those to whom it was relevant. Our interpretations are approximations born of respect for the images themselves and of a renewed feeling for the time. We are left to ponder one significant story born of cultural collision. The petroglyphs of Clo-oose have served us well. They have, like any great code, prompted us to express, and urged us to remember, what might otherwise have been ignored. They have brought some light to an obscure world.

“Petroglyphs, monuments, art, music, dance, poetry, etc. are at the core of any culture,” Peter Johnson told us in an interview. “Where a mix of cultures occurs, then look to its art as a means of understanding the complex motives of such clashes.”

Executed Today: It’s the “Gallows” that draws our site‘s eye but can you introduce the native-carved petroglyphs of Clo-oose, including glyphs of 19th century ships akin to the ones involved in your narrative? Twenty-plus years after your book, have these treasures become any better appreciated as art and cultural heritage, or any better preserved and curated at their site?

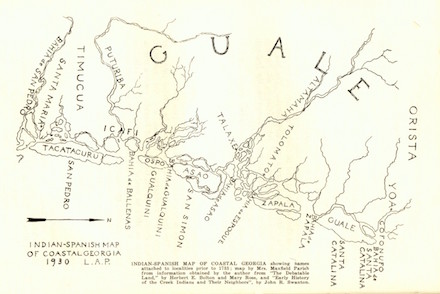

Peter Johnson: An excerpt of the Clo-oose affair from D. W. Higgins’s The Passing of a Race (Toronto: William Briggs Publisher, 1905) is included in the back of Glyphs and Gallows. Being directly facing the Pacific, the Clo-oose site is one of many that Higgins suggests captures Native / Indigenous interactions in the 19th century. The four ships at the Clo-oose Site, Higgins suggests, are: the Sparrowhawk (long thin one that the Royal Navy used as a gunship to apprehend the so-called guilty tribesmen who “murdered the crew of the John Bright as it foundered just offshore”); the John Bright (the other long one, a barkentine freighting lumber from the coast to Valpariso, Chile); and, the smaller two ships may have been ships that sailed to the site and “discovered” the bodies. The official name of the site (anthropologically speaking) is DdSf 1 or commonly called Blowhole Site, because of a spout of water that comes shooting out of a cleft in the rocky shore at high tide. Other sites nearby are Hill Site, nearby on a sandstone ledge showing a huge beaked bird, and a copulating couple. Southeast of Clo-oose about 6 miles away, is Carmanah Lighthouse; there is a site there that contains several petroglyphs of human figures (one seemingly impregnated with a child) and other sites nearby show huge, fat, birds, and various fishes. These don’t say anything we can understand about first contact with “whites” and are likely religious figures which had a role in Native cosmology or family organization.

Peter Johnson’s sketch of the Blowhole Site, circa mid-1990s: there’s no way to conclusively identify any of the ship images with any one specific vessel, but if we are to suppose that association then in Johnson’s estimation the ship at the top would be the Sparrowhawk and the one at just left of center at the bottom the John Bright. The image is (c) Peter Johnson and used with permission.

The maps, mention and location of the sites are no longer found in recent books about the West Coast Trail, and the sites themselves have been left to erode away along the shore. Since Glyphs and Gallows, there has been no attempt, that I am aware of, to cover, reveal or understand more of their cultural and artistic messages. It’s as if the Natives don’t wish any further trace of information to be transmitted to other cultures and perhaps, they don’t know any more about the sites than we do. For example, totem poles of other indigenous peoples are left, as part of their meaning, to rot in the bush. We have a different predilection, and that is to save objects from the past. Which is more important? Who knows? Perhaps, the one that serves the intent of the original artist is most important?

As sandstone erodes fairly quickly, these important cultural sites will be gone in 100 years. I personally believe they are very important artistically and historically. Were they found in Britain, like the monoliths on the Orkneys, (at Scara Brae) or Stonehenge and other henges, they would be covered and revered. Here, the new Natives at Clo-oose don’t seem to know much more detail about such petroglyphs at Clo-oose, or do not wish to preserve them as culturally important artifacts. Perhaps, too, they are too difficult to decipher, much like Champolion’s translation of Egyptian hieroglyphics, that previously to him took many hundreds of years. Native myths do not seem to be currently studied as much as they are simply appreciated … appreciation is good, but it’s only a start of understanding. Digging for meaning, beyond a purely aesthetic appreciation, is equally, if not more important.

One of the questions you set out to explore was whether these glyphs directly depict the events around the John Bright wreck and the subsequent hangings. Your answer is indeterminate on that … but how should we understand what they say more generally about the cultural upheavals concerning contact with Europeans, and about the civilization that preceded that contact?

The context of what happened during the first 50 years of European contact with West Coast natives, needs to be read about and understood by more “Whites” and Natives alike. D. W. Higgins believes whiskey traders destroyed many Native lives through the products they brought. (I don’t entirely believe this.) Higgins suggests in July 1858, the Native population in Victoria was 8,500, and goes on to say that at least 100,00 Natives perished from booze-related afflictions. I believe smallpox wiped out great numbers as Natives were moved away from Victoria up-country and spread the disease (like Covid), as they met other indigenous groups. Many were vaccinated, but Gov. Douglas at the time (1862), needed to save some vaccine for his own Europeans who settled in Victoria. They did not cruelly withhold the vaccine from the Natives, several European governors helped them as much as possible … that so-called dismissal today is a more popular misreading of the history of the time which serves a current, darker political purpose.

Once the idea that the John Bright survivors had reached shore only to be murdered by the Hesquiat got around, it’s comprehensible how a racist “tunnel vision” fit all facts into this understanding. However, I struggled with why this idea was initially formulated at all — it’s not the null hypothesis when a ship founders in a gale and nobody survives. Was it the shock value of “headless bodies” even though the Europeans on Vancouver Island should have been familiar with the devastating force of the surf? Was it a wholly cynical formulation by James Christenson to, as you put it, “elicit regular naval protection from Natives that he and other unscrupulous traders had cheated”?

Yes, it was a cynical formulation by Christenson and others to elicit naval protection from bald-faced raiding of their Native resources (lumber, fish, etc.). Shock value of the headless bodies certainly inculcated White racist reaction against Native action.

Victoria’s precarity at this moment, as a city that aspired to political leadership but was still a muddy frontier settlement, riven by class conflict, so bereft of women that they arranged bride ships — another of your books — and with a politically uncertain future between England, Canada, and the U.S. … felt eerily resonant with our treacherous current historical moment. Can we interpret the rush to judgment and the hangings here as to some extent expressions of a civic psychological insecurity? If so, did anyone involved in the prosecution later express any misgivings about it as Victoria grew and Canadian confederation became settled?

Yes I think so, not so much insecurity as fear. Myths had been perpetrated about Native violence (Natives attacked and killed white settlers on Lummi Island and in Cowichan Bay about this same time). So certainly, the Indigenous peoples gained much “bad press” about their time. That probably led to the gunboat frontier mentality of the time and the not-so-much later movement to remove the diminishing numbers of children in Native settlements to the White residential schools. This movement is usually interpreted as Native genocide on the part of ingigenous peoples and many Europeans themselves believe this. A few felt it was the only way to save what they believed was a dying culture by giving them proficiency in English so they could survive and integrate among a juggernaut of white settlers that became Canada. I guess the anxiety here is about the meaning on the word “integration.’

The debate over that issue remains. Too bad the petroglyphs are ignored today, they (and pictographs, etc.) could shed more light on the complex cosmology of the region’s Native cultures. Protest, and not an understanding of the historical context, seems to get more coverage. Real knowledge, not bitterness on both sides, is the answer. Proper historical co-operation would help immensely here.

One of the threads in your narrative is teasing out this undercurrent of skepticism about the verdict that stretches back to the European coroner who would not support a finding of homicide and includes the missionary priest Augustin Brabant, who extensively rebutted the D.W. Higgins narrative of native guilt … but only in private. Do we have any direct native sources from the time, or any later traditions, that tell us how the John Bright affair has been remembered in that community? And why did Brabant never publish his extensive personal knowledge from decades of living with the Hesquiat?

Father Brabant had a Catholic ulterior motive. His answer was to turn the Natives away from their own cosmology to a belief in Catholicism. That kind of religious zeal and “cultural blindness” led to the divisions we are trying to solve today. I bet very few remember the John Bright Affair or even care to, as an example and a means to dismiss and/or destroy early Native humanity. It took him years to write about his own view, likely because the Catholic Church would have condemned or excommunicated him.

[Brabant told Higgins in private correspondence that Christenson was at Hesquiat Village when the John Bright wrecked, but fled without attempting to render aid for fear that he would “expose myself to be killed by the Indians.” (That’s Brabant quoting Christenson at third hand.) Brabant thought Christenson only returned, weeks later, to cover up his own cowardice by bearing “to town a tale of cruelty, and barbarism, of which there is not a particle of truth.” Since Higgins extensively published the tale of cruelty and barbarism, it’s no surprise that he didn’t buy what Brabant was selling. Brabant also witnessed another shipwreck in 1882 — he wasn’t there for the John Bright itself — and described victims washing up on the beach in pieces, arms and legs horrifically torn from their torsos by the incredible force of the surf. -ed.]

* We lack a precise complement of the ship and especially of the women-and-children contingent, who were renumbered and rearranged by conflicting reports. Rumors that one or more of the children lived on as wards of this or that tribe circulated for years afterwars.

On this day..

- 1948: Ruth Closius-Neudeck

- 1566: Agnes Waterhouse, the first witchcraft execution in England

- 1598: Lucas, waterboarded Guale

- 1741: Not Sarah Hughson, "stubborn deportment"

- 1629: Louis Bertran, martyr in Japan

- 1938: Janis Berzins, Soviet military intelligence chief

- 1879: Kate Webster, of the Barnes Mystery

- 1969: Joseph Blösche, Der SS-Mann

- 1947: Three Jewish terrorists and two British hostages

- 1936: Aboune Petros, Ethiopian bishop

- 1600: The Pappenheimer Family

- 1747: Alexander Blackwell, who left them smiling

With impeccable timing she exited a life of proletarian obscurity by applying for a gig as a camp warden in July 1944, right when the Third Reich’s prospects for surviving the war went terminal.

With impeccable timing she exited a life of proletarian obscurity by applying for a gig as a camp warden in July 1944, right when the Third Reich’s prospects for surviving the war went terminal.

A Latvian radical back to

A Latvian radical back to  She was born Catherine Lawler in 1849 in Killane, Co. Wexford in what is now the Irish Republic and started her criminal career at an early age. She claimed to have a married a sea captain called Webster by whom, according to her, she had had four children. Whether this is true is doubtful, however.

She was born Catherine Lawler in 1849 in Killane, Co. Wexford in what is now the Irish Republic and started her criminal career at an early age. She claimed to have a married a sea captain called Webster by whom, according to her, she had had four children. Whether this is true is doubtful, however. The actual execution of the sentence of death had changed a great deal over the 11 years between the

The actual execution of the sentence of death had changed a great deal over the 11 years between the